from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 11

I am not sure why I asked Kerry Schuss if he had made work before he was a dealer. Something just vibed with me, and as it turned out he had recently brought boxes out of storage of Kirlian photography he had made in the late 1970s. He flipped through these surprising prints, a compelling abstraction grown out of his experimental exploration of materials. There is a vividness to these images which radiate the energy and excitement with which they are made. Their contemporaneity is apparent, having much in common with materially directed photo practices today. Their vintage physicality is also a part of their power, the rich depth of saturation achieved with paper, electricity, a conduit and light.

BY LEE PLESTED

KERRY SCHUSS

Charges

In 1976, when I was twenty-four years old, I moved from Columbus, Ohio, to New York City to become an artist. At that time I was making abstract paintings influenced by Mondrian, Malevich, Rothko, and tantric art, all of which I had only seen in reproduction in books. I had read that Mondrian was involved with Theosophy and I got a hold of the book Thought Forms by the Theosophists Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater. Having been a good hippie, it was in this intersection of reductive abstraction and spiritual quest that I found subject matter to explore.

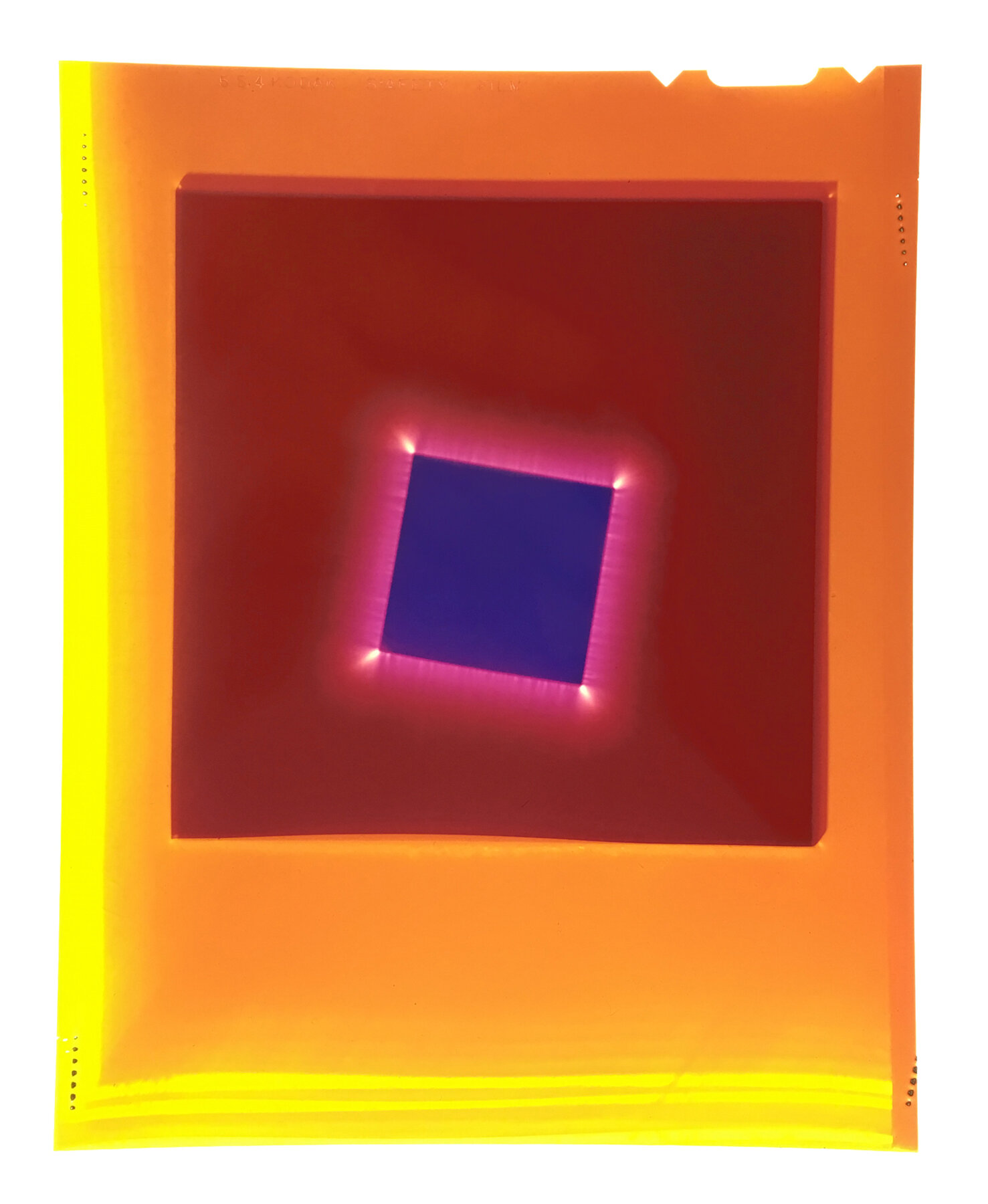

In New York I visited museums and galleries, and for the first time I got to see great art in person. This was thrilling, but also over- whelming. Trying to paint in New York proved to be difficult for me because my mind was filled with other artist’s imagery. Around this time I bought a Polaroid SX70 and started experimenting freely making abstract photo- graphs. The SX70 film had the capability of very rich and saturated colors. I played around using colored lights and reflections off plastic to make instant painterly effects in its small square format. In the magical, chance-like qualities of the SX70, I found the open space to create my art.

In late 1977, I saw an ad in the back of the Village Voice advertising a workshop in Kirlian photography. In 1939, the Russian inventor, Semyon Kirlian accidentally discovered the technique of using high voltage to create a corona discharge to expose film. This technique, also called electrophotography, was the subject of research in parapsychology and alternative medicine. In short it was believed that the photographs captured a living form’s aura. It was thought to be a visual measurement of the energy fields around living things. At the workshop, I learned the basics of Kirlian photography and how to fabricate a device to make such images.

The device I made used a Tesla coil that generated high voltage with very little amperage. There are photos of Nikola Tesla, from the turn of the last century, with sparks surrounding his body demonstrating his invention. I connected the Tesla coil to a cop- per plate that was housed in Plexiglas and connected to a timer. In a totally dark room, film was placed on the copper plate and the subject, such as one’s fingertips, are placed directly in contact with the film. That completed the circuit creating a spark. It felt like a shock of static electricity.

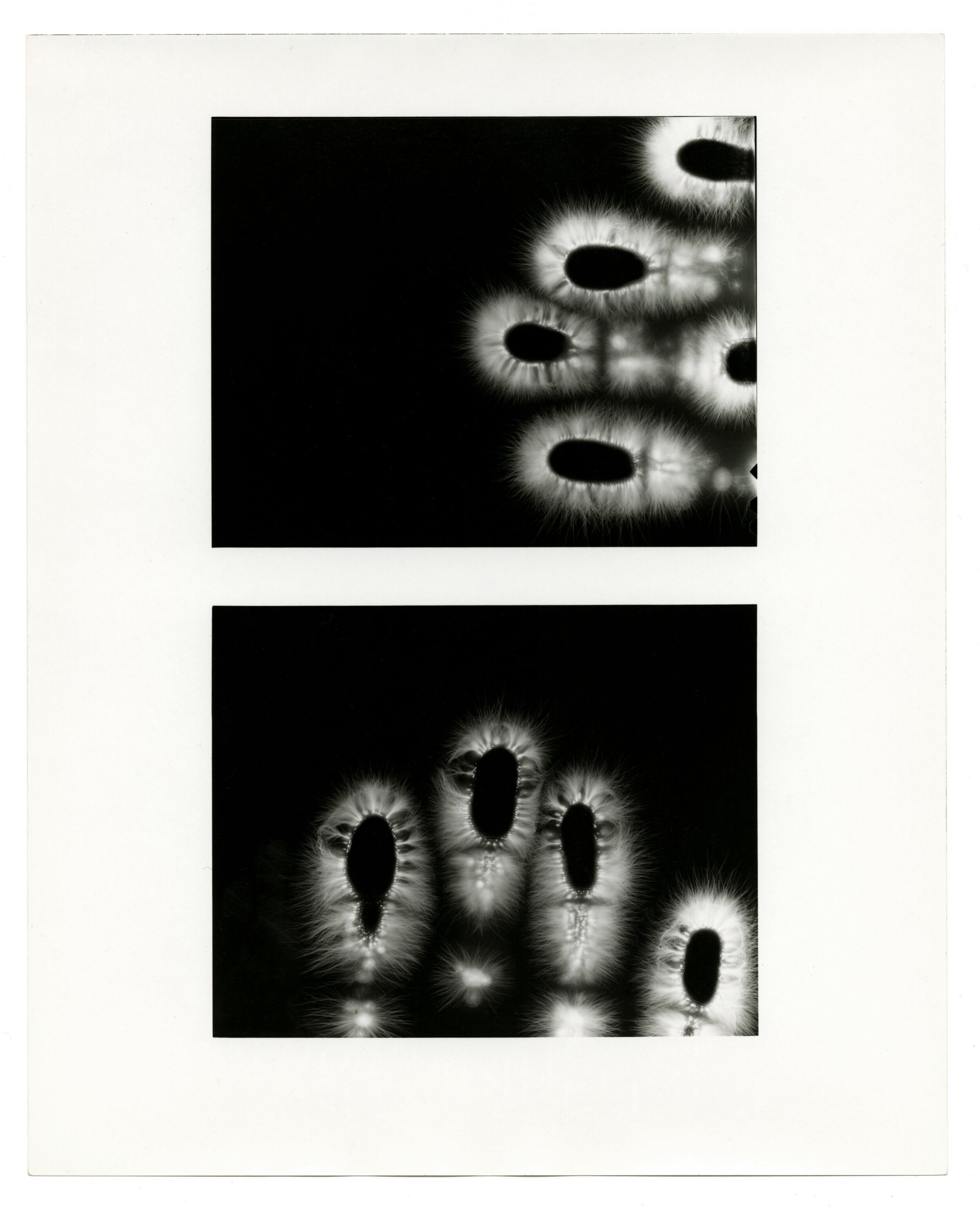

My first photographs were typical of other Kirlian photographs of fingertips. When friends came by my studio, I would make a Kirlian of their fingertips and referred to the resulting images as “Portraits.” Most people were happy participants, curious to see their aura. Initially, I used SX70 film, which was fun because it yielded immediate results. In the darkroom, I would break open a pack of SX70, zap the film with electrical current, and run the exposed film through rollers I took off a camera. In seconds the subject’s aura appeared. The electric blue circles created from the shape of their fingertips floated over the shiny black square film making almost limitless compositional variations.

Squares Electrified II, 1978

Squares Electrified I, 1978

At first, I honestly believed the photos were actually capturing auras. Remember, this was the 1970s when many people genuinely believed in missions of this nature. As my technical abilities grew, I began to realize these renderings were more affected by the device and materials than the psychic powers of the sitter. So the work evolved to be less about revealing auras, and more about exposing film in abstract compositions in the dark. I looked for other things that conducted electricity and created a spark. After experimenting with found pieces of metal, I made some copper squares and circles of varying sizes that became both tools and subjects.

At that time, John Cage was actively performing and his ideas influenced the whole art world. Because my darkroom had to be totally dark, it caused a loss of control to some degree and this foregrounded the element of chance. It also opened up the world of cameraless photography and its long history. Man Ray’s rayographs and Moholy Nagy’s photo- grams are well known examples, but there were many other artists that I looked at who made emanations on film and photographic paper including Christian Schad and Lotte Jacobi.

I started to experiment with other photo- graphic materials to see how they would react to an electrical charge. Black-and-white film had the capability of a full tonal range of values from blown-out whites, to very subtle grays and blacks. I worked with 4x5- and 8x10-inch sheet film and made several series of fine grain contact prints from the negatives. Along with the black-and-white film, I zapped 4x5 sheets of Ektachrome that turned electric blue and had an astral quality. In look- ing to expand the palette of colors, I started to experiment using colored lights in combination with the electricity. The colored lights produced saturated colors and patterns to which the electricity affected in unpredictable ways. Cibachrome was popular at the time as a way to print color slides and film and a way to achieve unusual rich colors. Like the SX70 film, Cibachrome responded very well to a direct electrical charge. I made numerous one of kind pieces, some as large as 11x14, by the end of my Kirlian explorations in 1981.

All of these photographs were created in a loft above Max’s Kansas City, where I lived from 1976 to 1981. It was a raw 2000- square-foot space with floor to ceiling windows overlooking Union Square and the rent was $175 a month. This was Max’s after the Warhol years, but still a great period, because for those few years, the main venues to experience new music were CBGB and Max’s. The bar was on the ground floor, the music was on the second, the dressing rooms on the third and I was on fifth floor. I got to hear much of the punk era whether I wanted to or not. The sounds and reverberations on my floor were ever present, and in retrospect, most likely added to the electricity in the photographs.

My five years living above Max’s came to a sudden end in 1981 when the club’s bouncers stopped me from going up the stairs. They told me emphatically that the owner wanted me to move out. Having seen them do their dirty work previously, I packed up and left. This brought my experiments with Kirlian photography to an abrupt end. The boxes of prints, negatives, and chromes went into deep storage, and I stopped thinking about them long ago. I did not open the boxes until this year—thirty-five years later—when Mitchell Algus mentioned that he was organizing a group show of 1970s photography. Stored together with the numerous photos was a film box filled with a few dozen 45 rpm records, including hits like Devo’s first, self-published single (“Are We Not Men”), Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel,” and The Cramps’ “Human Fly,” which I bought during those years above Max’s for dance parties at my loft. Together, the records and photographs form a time capsule, a visual and aural diary of my life.

BY KERRY SCHUSS

Double Self Portrait, 1979

Untitled, 1978

Untitled, 1978

Untitled, 1978

Untitled, 1978

Untitled, 1979

Untitled, 1979