from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 6

Michael St. John:

The Paranoid Style in American Painting

By Christian Rattemeyer

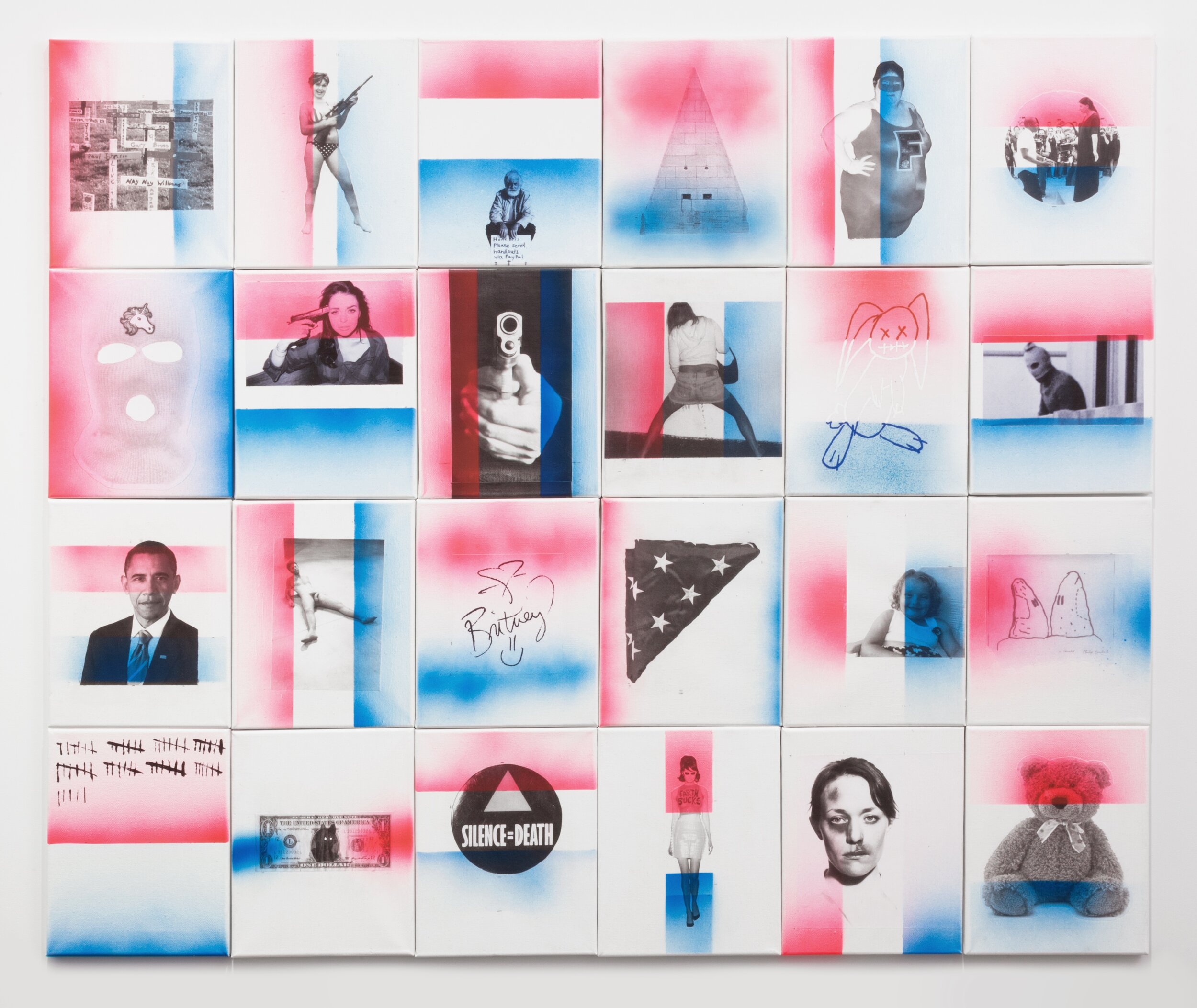

An Assembly of Mayhem (2013)

Michael St. John might be the best-known artist you never heard of.

In certain pockets of the art world, he is highly regarded as the teacher, mentor, and loyal friend to a younger generation of artists, including Nate Lowman, Dan Colen, Dash Snow, Alex McQuilkin, and Josh Smith. Though this artistic lineage becomes immediately apparent once the shared trajectory of styles, interests, sensibilities, and subject matter is acknowledged, St. John’s own critical vision has often been obscured by the popular success of these younger artists. Furthermore, St. John’s peers Richard Prince and Cady Noland are often cited to establish a context within which St. John’s performance is relegated to the role of supporting cast. What is lost in both in- stances is St. John’s generationally specific cultural sensibility that I would characterize, in the famous term of Richard Hofstadter, as the “paranoid style.” If there is little in St. John’s critical reception to suggest this approach and its validity, then it is mostly for the fact that too few discussions of St. John’s work have embarked to locate his practice in any critical discourse. In fact, few artists of St. John’s seniority and influence have been written about as little as he has.

Michael St. John’s work is surprisingly varied, ranging from trompe-l’oeil painting to collages made of cut-out magazines, skateboard stickers, and pop cultural material, to sculptures made of cast plaster and found objects. His motifs often include violent scenes, softcore porn, and advertising images of pop stars and fashion models, graffiti of profanities, slogans, and scribbles, as well as reproductions of menacing, catastrophic, and otherwise horrific messages gleaned from the mediated cast-offs of American life. His strategies of appropriation and assemblage, painting and collage point to the underbelly of the (often poor, white) American experience; it is an aesthetics of trailer trash, a kind of FEMA conceptualism.

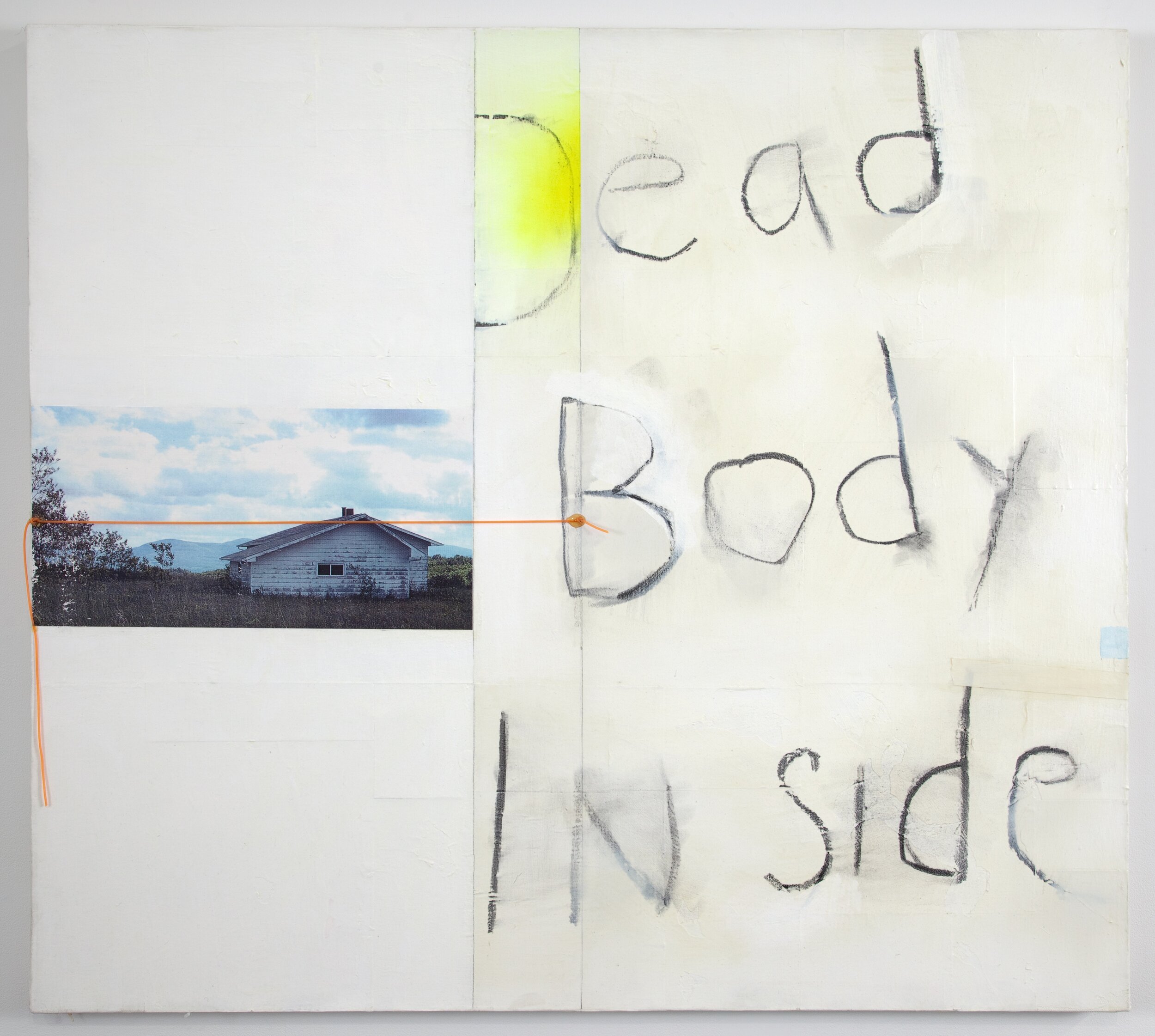

In the painting Dead Body Inside (2006), the photograph of a flood- damaged house (presumably in the wake of Hurricane Katrina) has been collaged onto the left side of a canvas bearing the titular graffiti; a tacked string of red wool, stretching from the left edge of the canvas across the image at the level of its roof peak suggests the waterline of disaster. The question of race, always connected to the question of poverty and the history of American violence, is never absent from St. John’s work. In Negroes with Guns (2007), a series of seven paintings, collaged images of African-American radicals, including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., are overlaid with a transparent red spray- painted square. St. John finishes each portrait with another layer of graffiti by applying variations on the stenciled slogan from which the series gets its name. Maybe most jarring in its economy of means and ambiguous directness is October (2014). A torn, purple sheet of paper glued on to white canvas depicts the photocopied image of a young, black woman with a black eye that has been stitched above the brow. The word october has been type-written below in lowercase letters. Like a torn sheet from a wall calendar, the work denotes that which has just happened—in this case, an act of casual, daily violence against women—all the while poking morbid fun at the bible of art historical discourse, October.

The confrontational nature of October is similar to that of a paint- ing made the same year titled Fear (2014), of stocking-masked faces overlaid with variously colored bands of spray paint. The graphic ambiguity of these works may have caused them to be dismissed as morally ambiguous, racially insensitive, politically incorrect brute humor. But St. John’s work is misunderstood when read as an honest expression of white male revenge fantasies or cheap revolt. Instead, St. John presents us with a symptomatic read of the American visual landscape. His subject is an America of petty crimes and cheap thrills, a country saturated with the imagery of banal evil. The work An Assembly of Mayhem (2013) is a veritable inventory of St. John stock material, ranging from images of bikini-clad girls holding machine guns, teddy bears, mug shots of domestic violence victims, his own paintings (such as Shooter), a folded American flag, a dollar bill, Philip Guston paintings, icons of AIDS activism, and Britney Spears’ fake-spontaneous scribbled signature—all simulacra of stylized revolt.

Michael St. John was an adolescent when in 1964, a year after the Kennedy assassination, Richard Hofstadter wrote his classic essay for Harpers, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” in which he introduced a provocative term to describe the emergent right-wing shift in American politics: “I call it the paranoid style because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind.” By tracing the paranoid style from the Founding Fathers all the way to McCarthyism and Barry Goldwater, Hofstadter categorizes it as a quintessentially American trait—an encompassing philosophy of exceptionalism and moral absolutism laced with violence, sexual energy, and renegade redemption. The fact that the paranoid style reared its head at a time when St. John was coming of age—during a time of genuine social change and unrest, the civil rights movement, and a period of political assassinations unbecoming an advanced nation in the late twentieth century, suggests a crucial difference between the generation of St. John and that of his students. It is easy to become tone-deaf to the paranoid style, misunderstand its root in urgent observation, and ridicule its form as obsessive and pedantic: “it is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant,” Hofstadter wrote; and St. John inherently understands this.

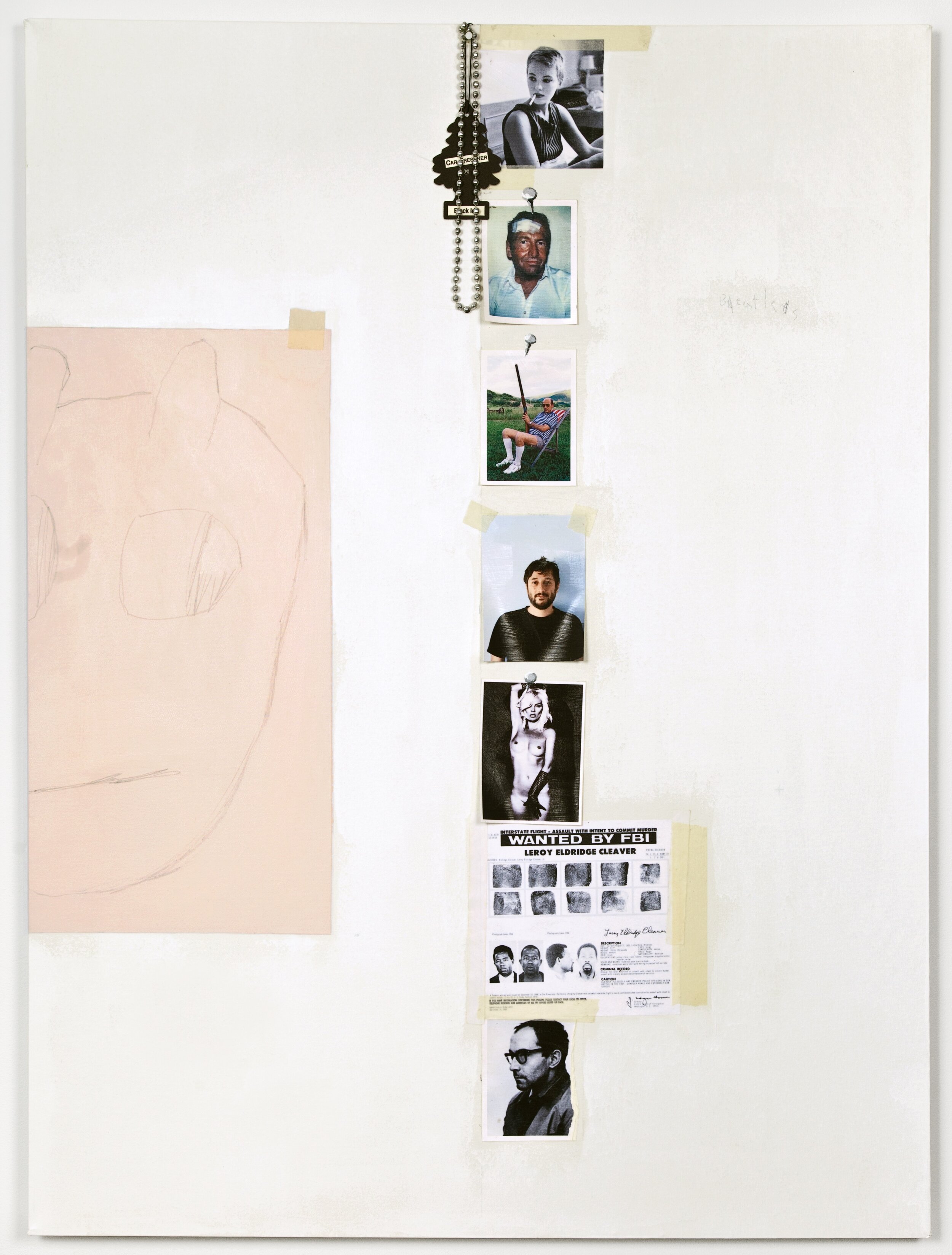

The paranoid style in American painting may be best exemplified in St. John’s series In the Studio Twenty Eleven (2011): assemblages of pictures of artists and filmmakers, fashion models and “Wanted” posters, scent trees and dog tags, annotated by hand-scribbled messages and neatly sorted by the maniacal order springing from the fantasy of apocalypse and conspiracy. St. John shows us the double suffering of the paranoid that characterizes America today: “afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well.”

Negroes with Guns (2007)

Sexy Back (2009)

Dead Body Inside (2006)

October (2014)

In the Studio Twenty Eleven (2011)