from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 14

Calvin Hewitt, 1973

DAVID OGBURN

INTERVIEWED BY LESLIE HEWITT

David Ogburn’s images helped shape my conception of the world as an artist. His images filled my home in particularly personal ways, with his photographs of my mother, father, grandmother and pop-pop (grandfather) as part of my family archive. My father, inspired by David Ogburn, his childhood friend, purchased a 35mm Pentax manual camera. This camera became the camera I learned from. I have studied Ogburn’s images, researching his composition, angles, movements and visual accounts that describe the fullness and complexity of Black American life through the documentation of cultural icons in music, politics, theater and cinema. Like a tidal wave coming out of the sixties into the late twentieth century, his positioning of the glossy with the grit, the elaborately sequenced with the ascetic, and the joyful experiences with the disheartened all find representation in his vast collection of images.

In late December, I had the opportunity to visit David Ogburn in his studio in Rock Creek Park, Washington, DC, and speak with him about his approach to stopping time.

Martha Hewitt with her eldest son in New York City, 1971

Skyy (a.k.a. New York Skyy) in Richmond, VA, at radio station WANT-AM, 1981

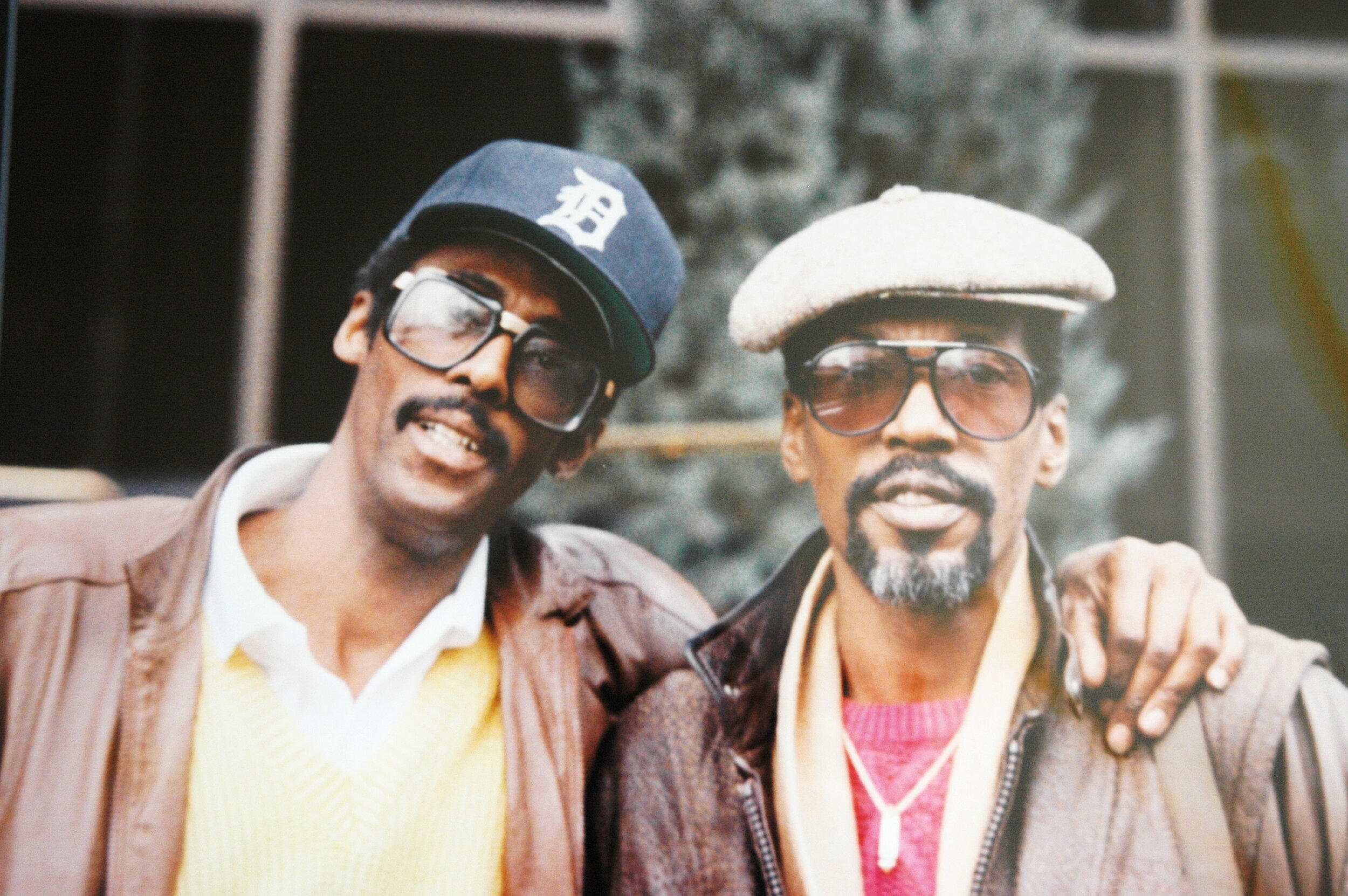

David Ruffin and Eddie Kendricks from The Temptations in Baltimore, MD, 1988

Earth Wind & Fire at Constitution Hall in Washington DC, 1973

Coretta Scott King and Stevie Wonder with Congressmen Robert Garcia, Thomas Philip O’Neill Jr. and John Conyers, 1982

Stevie Wonder presenting to Congress the petition request for Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday, 1982

New Edition at The Wiz in Washington DC, 1983

Chaka Khan, 1984

Sade with band members resting in a limo, 1985

Congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Dorothy Height with Vice President Gerald Ford, 1973

How would you describe your photographic eye?

When I got into photography, the pictures that I took had to be interesting to me. They had to have something to give. I would be in one position and would shoot an entire roll of film in order to get a great shot of something, something that you could feel. I have been blessed with enjoying photography and being able to make a living from it as a profession. To be honest with you, I am not used to speaking about my photographs.

New Edition at The Wiz in Washington DC, 1983

They speak for themselves surely!

You know, if you love something you get into it heavy and that’s what I did with this photography thing. I never went to school for this as an art form. I am pretty much self-taught when it comes to the technical knowledge. Taking pictures, developing the film and printing the photographs were all a process. I set up a studio and began to work through the details and develop a way of working. I did fall in love with the work of Gordon Parks and James Van Der Zee, but that came later. My education came through spending time with the people and places in my pictures.

Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, 1976

Chaka Khan playing backstage in New York City, 1984

This may seem like a strange question: what do you think shaped your notion of beauty? Your pictures are full of photogenic moments in the most unexpected circumstances. In that space I find beauty, like a sort of collaboration between the circumstance and you sealing the moment, at the right moment. What do you think helped you recognize such moments through the lens of your camera?

It was my individual nature, I guess. It was a combination of what I saw and what I knew was there in the person or in the moment. Sometimes I would walk around the streets with my camera around my neck and shoot, develop, print and feel surprised at what was captured. But ultimately, I feel that family is really what shapes what you see through the lens. At one time I became the president of my family reunion, when we had over 300 living relatives. You start out documenting the world around you, documenting your history and seeing value in it. I read the work of Dr. Chancellor James Williams, who was an African-American sociologist, historian and writer. This connected me to the importance of history and not to take it for granted. This translated well into how I worked with photography and my subject matter. It also shaped a confidence that a saw in people beyond assumptions or quick conclusions. The research of Chancellor Williams and my life experiences helped shape an outlook that included a deep respect and value for black life. Growing up in New York most likely helped, including my sister inviting me to listen to the music of Art Blakey, an important American jazz drummer, and traveling to Egypt all shaped and opened my eyes.

Minnie Riperton onstage at Cramton Auditorium at Howard University, 1973

Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) and Gil Scott-Heron, 1979

Over forty years of images, I am so impressed and in awe of your albums. Thank you for sharing them with me in your studio. While speaking with you and looking around your studio—walls covered with photographs, screens full of virtual archives and hard copies in physical files—certain words and couplings of words came to mind. I would love to share the free association with you, and please comment if you wish: access and trust, celebrity and vulnerability, grit and glamour, bright lights and dark rooms, unexpected style, power and political positions, highlife and electricity.

Access is the key. I started working with WHUR-FM, Howard University’s radio station, in 1970 as a photographer adding to the station visibility and visual archive. I also began teaching photography to young people through the District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency around the same time. Look, I fell in love in the darkroom, developing film and printing pictures, and eventually became the principal photographer in the District of Columbia for a number of national record companies like Motown, Philadelphia International, Arista, BMG, PolyGram, CBS/SONY, MCA and Warner Brothers. In a single day, Jesse Jackson could be at the radio station, along with Roberta Flack. . . I would think to myself, do you have enough heart to do this, to be in the same space with so many important people in the community? I made contact through my work with representatives of record companies and began to represent the mid-Atlantic region, from Philadelphia to Virginia Beach. Andre Perry, the first music director of WHUR-FM and a good friend, would tell the record companies about “360 degrees of blackness.” Perry would play entire albums in that spirit. It also made the metaphoric argument that extended to visual representation. Black musicians should be photographed from the perspective of a photographer who knows the culture from being a part of it, thus completing the circle. Working in that time period included the possibility of photographing musicians, politicians and civil rights leaders all intersecting and sharing space and time together in ways that reflect back the spirit of the sixties. I was able to photograph for the annual Congressional Black Caucus dinner and the National Association of Black Owned Broadcasters. I have the exact dates somewhere here.

Earth Wind & Fire at Constitution Hall backstage, 1973

How to author the fullness of black life in the United States? Coming out of the sixties, transitioning into the seventies, what was shaping black visual representation both politically and culturally? The support for one another is so elegantly and effortlessly captured in your photography. You were there to capture such . . . incredibly important moments.

I wonder if this is why the candid shot feels so critical—the unexpected and perhaps the more venerable moments in your portraits. Is this what makes them iconic? You seem to be able to capture the personal, more intimate sense of self along with the subject’s public persona (the rehearsed, presentable and branded) simultaneously.

I went away to school, in 1961, to Saint Paul’s College in Virginia, and my good friend Thomas Foster went to Virginia Union University. Your father was in the U.S. Air Force. Black music wasn’t center stage back then and often it was a parallel world in many ways. In the sixties, before we went out, we would have to press our pants, shine our shoes, put on a shirt, tie and jacket, and that was to go to a party. When the seventies pulled around, things got a bit looser.

The darkroom was my life. Studying the human condition (Ogburn received a B.A. in Sociology in 1968 and an M.A. in Urban Studies in 1973, both at Howard University) helped me understand what was going on with our people.

Phyllis Hyman in Washington DC, 1977