Carmen Winant

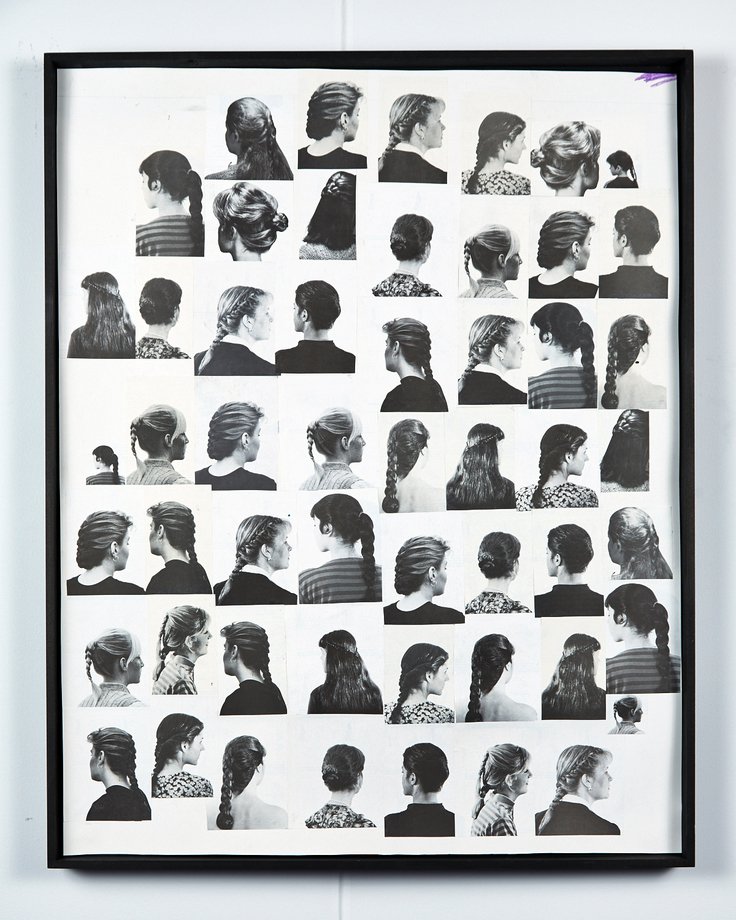

White Women Look Away, 2017

Found images

32 x 38 in

Courtesy of the artist

Carmen Winant

by Drew Sawyer

(originally published in OSMOS Magazine Issue 13)

In 1969, during the Female Liberation Conference at Emmanuel College in Boston, a dozen women met to discuss health issues and share experiences with doctors. Realizing that they lacked access to useful knowledge about their bodies, the group began gathering information and formed what would become the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. In 1970, they published a newsprint booklet based on a class at MIT, "Women and Their Bodies,” that combined careful research along with first-person accounts and images. It was revolutionary for its frank representation of sexuality and for the way it put women's health in political and social contexts. The publication became an underground success and was soon republished under the name Our Bodies,Ourselves in 1971, followed by an expanded, commercial edition in 1973. While Carmen Winant was born more than a decade after the initial publication of Our Bodies,Ourselves, her life and work have continued to be informed by its legacy. When she was a teenager, her mother gave her a copy of the first edition. For a recent body of work, including Our Faces Belong to Our Bodies (2017), she lovingly collaged and drew over images clipped from its pages.

Winant often refers to the period of second-wave feminism, but her work is never nostalgic. It complicates and expands the original narratives of her source material—much of which she has patiently collected from used bookstores and garage sales over the years—through the dialogic effects of montage. What does feminism look like today? And what do the feminisms of the past look like through the lens of the present? As both an artist and a writer, Winant continually investigates these fraught questions. She has written extensively on related topics from Germaine Greer to representations of childbirth to contemporary selfie culture and feminism. A recent large-scale wall installation, Pictures of Women Working (2016), at Ohio’s Columbus Museum of Art, comprises more than one thousand photographs, gathered and cut from various 1970s publications. Collaged on top of recent newspapers, the montage reconsiders what constitutes work for women, both then and now: beautifying, sports playing, nursing, protesting, art making, and sex, among other activities. More recent found images of Mothers of the Movement appear alongside Jane Fonda workout stills and photographs of well-known twentieth-century artists in their studios.

Deftly mining the politicized history specific to the photomontage, Winant invokes the spirits of Hannah Höch and Martha Rosler. Yet, where as these artists cut, rearranged, and juxtaposed photographs from mass media to create new pictures, Winant keeps her found pictures whole and separated. The result is a collection that opens up or distills new meanings.What can we glean from representations of women working, both during the heyday of second wave feminism and today? What qualifies as labor? What are the limits of representation when it comes to women and history? In many instances, viewers have felt empowered by Winant’s work or read it as a celebration of progress. Perhaps this is because she began making the work during Hillary Clinton’s presidential election campaign in 2016, when the future was looking a lot brighter. But already the artist was learning about Ivanka Trump’s #WomenWhoWork initiative (and now book) and thinking about the old feminist principle of finding liberation through work outside of the home.

Pictures of Women Working wrestles with the ways that second-wave feminism’s focus on work as economic independence hung on a specific vision of equality that mostly fit the interests of middle-class white women, while working-class women, often of color, were already in the workforce. As bell hooks has pointed out in her book Feminism is for Everybody: “When reformist feminist thinkers from privileged class backgrounds whose primary agenda was achieving social equality with men of their class equated work with liberation they meant high-paying careers. Their vision of work had little relevance for masses of women.”

Another recent work, White Women Look Away (2017), is perhaps a rejoinder to hook’s essay. The collage gathers black and white photographs of hairdos belonging to young white women, who all sport various braids and buns. At first glance, the images appear to be a salon window advertisement. But its title suggests other possible connections. Do the women turning their backs away from the viewer represent the majority of white women who voted for Trump? Or perhaps they are the organizers of the 2017 Women’s March who failed to include any women of color or see the how overlapping identities beyond gender—including race, class, ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation—impact the way women experience oppression and discrimination? Winant’s work may not provide answers, but it seems to be posing the right questions.

Installation view of Grey Matters, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH, May 20-July 30, 2017

Carmen Winant

Our Anger is Changing Our Lives, 2017

Found images, dye

22 x 30 in

Courtesy of the artist

Carmen Winant

Remember the Dignity of Your Womanhood, 2017

Found images, dye

22 x 30

Courtesy of the artist

Carmen Winant

What Would You Do If You Weren’t Afraid?, 2017 (detail)

Graphite, images of women in the news before November 8, 2016

Overall dimensions: 22 x 40 ft

Courtesy of the artist