Mary Kelly

Circa 1940, 2016

Compressed lint and projected light noise

95.5 x 127.5 x 1.5 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

MARY KELLY: NOVEMBER 7, 2017

interviewed by Ramsey Kolber

(featured in OSMOS Magazine 14)

Ramsay Kolber: It is my understanding that “Circa 1968”, was the first of the “Circa Trilogy” works to be produced and was originally shown in the 2004 Whitney Biennial. When you made the work at that time, did you conceive of it as being part of a trilogy or was it seen as an expression of that particular moment that you returned to later?

Mary Kelly: That’s a good question, because it points out that all of my work is project-based and much of it takes place over several years. Sometimes I don’t predict where I’m going to end up, while other times I do, but I think this was the beginning of what became a rather extensive reflection on the history of my era. For me, it didn’t start with thinking about myself or where I came from—it was your generation who kept asking about that period. It seemed particularly pointed during the second Gulf War, when people were bringing out slogans from the past. I remember seeing one in particular at UCLA that said, “Stop the War, Have Sex” and I thought, that’s kind of close to, “Make Love, Not War,”,but not exactly.

RK: Similar, but a little bit removed...

MK: So I started to think: “Isn’t it interesting that people who are born around that time,1965 to 1989 even, seem to have this intuitive knowledge of what their parents went through?. There’s this way in which they are trying to decode parental desire. Issues like: What do they want from me? Why did they fail? Of course, I was a post-war child. We were, perhaps unconsciously, survivors; the children of the people who were left, and we grew up really trying to promise that it would never happen again. I think when the Vietnam War happened there was both this shame and commitment to end the war. It kind of came full circle after ’68.

RK: As your were speaking, I was reflecting on Griselda Pollock’s text After-affects /after-images and this idea that as “children of the survivors” as you say, we carry the memory of traumas we ourselves did not experience. Rather they live within us as a type of transfer or residue, a holdover from those that came before us, in such a way that when another moment has the echo of that experience in our own present, we cycle back to that feeling. This idea of the transfer or trace of the past seems present in your use of the lint medium.

MK: I had originally developed the lint medium to deal with war crimes. Over time, I thought perhaps it is also suitable for or evocative of the idea of historical memory, and maybe I can make an image, even though I don’t generally work with images. So I went back to my own archive and found this image of ’68 that had been so present. It was interesting as it seemed to me to be about the image, and to be about certain powerful, iconic images that dominate our dreams and desires in a way that only those really over-determined moments in time and images can. So this was one of them and that’s where it started. After that, I started to think more broadly about what I call the “political primal scene,” drawing on Freud’s idea of the child’s question of: “Where I did I come from?” that is usually answered by filling in a kind of fictitious past. I was thinking more about how the past appears in the present, as a way of trying to deal with your current situation.

RK: In thinking about the beginnings of “Circa Trilogy,” I wondered if you could speak a little about your related “Unguided Tour” prints, which are part grid and part narrative text. These works opened your recent show at Mitchell-Innes & Nash and have a one-to-one relationship with the individual works in the trilogy. While they are not “footnotes,” as in the case of earlier projects like your “Post-Partum Document” (1973-79), they do act almost like an index or matrix for these larger works in the way they’re laid out, visually and textually. What was the original conception for these works and how you see them functioning in relation to “Circa Trilogy”? I have even heard there was an instance in which they were performed.

MK: Yes, I thought of them as a kind of imaginary mapping. I have always done a lot of writing, and I felt like I needed to do that. The first one was written in 2004 at the same time as “Circa 1968,” so that was really the model for the second and third pieces.

RK: There is a line that recurs across these prints: “I was behind you / the photographer seconds before the shutter clicks immuring the moment / not long before you were born.” It is the only line that echoes through each of these texts, which in a way has the feeling of a Greek chorus whispering in the ear of history, but also is structured poetically like the duration of time. There is this reference to both a past—of a “behind you”—not only spatially but temporally, but also you are not yet born, so that this future also still holds potential from your place in the present.

MK: And it positions you each time as a different generation.

RK: Exactly, so that in each moment there’s this capture of an image. The word “immuring” is so precise, because it is also this confinement of a particular point in time in the same way the image is the capture and constraint of a particular moment, but there is also a sense of recurrence.

MK: For me repetition evokes a psychoanalytic point of view: how Freud talks about remembering, repeating and working-through; that these iterations are a way of remembering and of working through the consequences of those events. I thought a lot about Walter Benjamin and his saying that the present generation has a secret agreement with the past, and that that secret agreement sort of turns around the idea of missed possibility. Recently, I started hearing people talk about the end of an era, when Stuart Hall died and now Linda Nochlin, and I started thinking: is it the era of a certain kind of vision of the future? This seemed to be the most important element as I went on with the work, to be kind of reoccurring, the seeming failures of these moments, and what it was in the past that was bearing on the present and the future, as the project or lack of it.

RK: So it is this idea of looking back at those times as a way of envisioning those projects that, while you could not see them at the moment, had potential to be realized in the future, whether they actually were or not.

MK: That’s why I kind of latched onto Hayden White’s idea of the “practical past.” When the story of where you came from is a sort of grand historical narrative, it also becomes about social change. Of course, you know the phrase the “personal is political”–it is a reflection on how you live your everyday life. But it is also the way in which the personal and the political are connected, almost like a Mobius strip.

RK: This is obviously something that was relevant in 2004 when you first made “Circa 1968,” this idea of engaging with the past in the present, but you’ve also mentioned the current political moment feels like a return to many of the same issues we were grappling with in the past. In thinking about our present, did you feel there was a sort of urgency to show works like “Circa Trilogy,” as well as your other series like “7 Days” and “News from Home” that address the 1960s and ’70s, or was it seen as a more general engagement with history?

MK: Yes, well I consider it to be a reflection on history. There are works that have amore activist intention. I’ve always considered myself to be something like a participant observer: I want to witness history to address the questions it raises. I had already done this kind of work before Trump was elected, but it kind of changed the way I saw it, the repetitions—when I read Nixon in one of the letters from the “News from Home” series: his escalation of the war when he had promised peace, remembering how he got elected, and the desperation after. Everyone was defeated, the potential had been squashed. It is interesting, not just at this moment in time, but with a kind of shocking awareness of what a short period of history is and how repetitious these issues are and certainly where we find ourselves right now, where we feel like its back to square one, starting over. But in some ways it is important for us to wake up and see that things are never finished.

RK: And never resolved. At present, there is a lot of conversation around truth, or truth-telling, and the function of the media. I think in previous texts you’ve said journalism and the news filter into your work insomuch as art becomes a space for a visualization of and reflection on the issues at hand. Much like your use of the lint medium, there is a similar sense that the media is filtered through something and mediated or recast by its impression.

MK: I would say the trace...

RK: Yes, the trace of a particular moment or narrative. Returning to the iconic function of images that you mentioned earlier in relation to “Circa Trilogy,” the images you used for “Circa 1968” and “Circa 1941” were staged photographs, yet they were seized on in their present moments as truth and passed into history as emblematic of a time. How might this now reflect on current conceptions of “fake news,” and the questionable truth of images?

MK: One of the things Hayden White insists is that objective or so-called “factual history” has a place, but there is also a place for the history of memory. That even if we’re getting it slightly wrong, that it is giving us ideas about how we can deal with our situations.

RK: That it is still constructive.

MK: It is what he calls “tactics for living.” I was very careful in the “Circa”project to stage the images with projected light noise, so that one can be aware of that uncertainty.In terms of people’s understanding, the events of their time and how they deal with them is always a continuous negotiation of truth, which is a certain kind of critical engagement that is very different from the idea of endorsing fake news. Yet this idea touches on something very important that is beyond what I take on as an artist, but it is how all of us that are involved in the arts are, and have been for some time, involved in a project of deconstruction. We are now faced with a moment in which that is still a necessary reflection, but it isn’t good for mobilizing people to act. When you’re up against horrible right-wing ideology, you sort of need a counter ideology, as Stuart Hall said. In order to make a movement, you need to know what you believe, rather than to simply resist or say “no”to what’s in place.

RK: It is almost that this urgency to act comes not just from saying “no ”to something, but knowing how to define yourself out of that which you are not—that actually action has to come from a sort of self-realization, not just resistance.

MK: We actually spent a lot of time through the ’80s and ’90s being suspicious and thinking critically about ideology and then kind of finding ourselves in a situation, where we know we have to do that and acknowledge there has to be some vision—but I don’t have an answer for that.

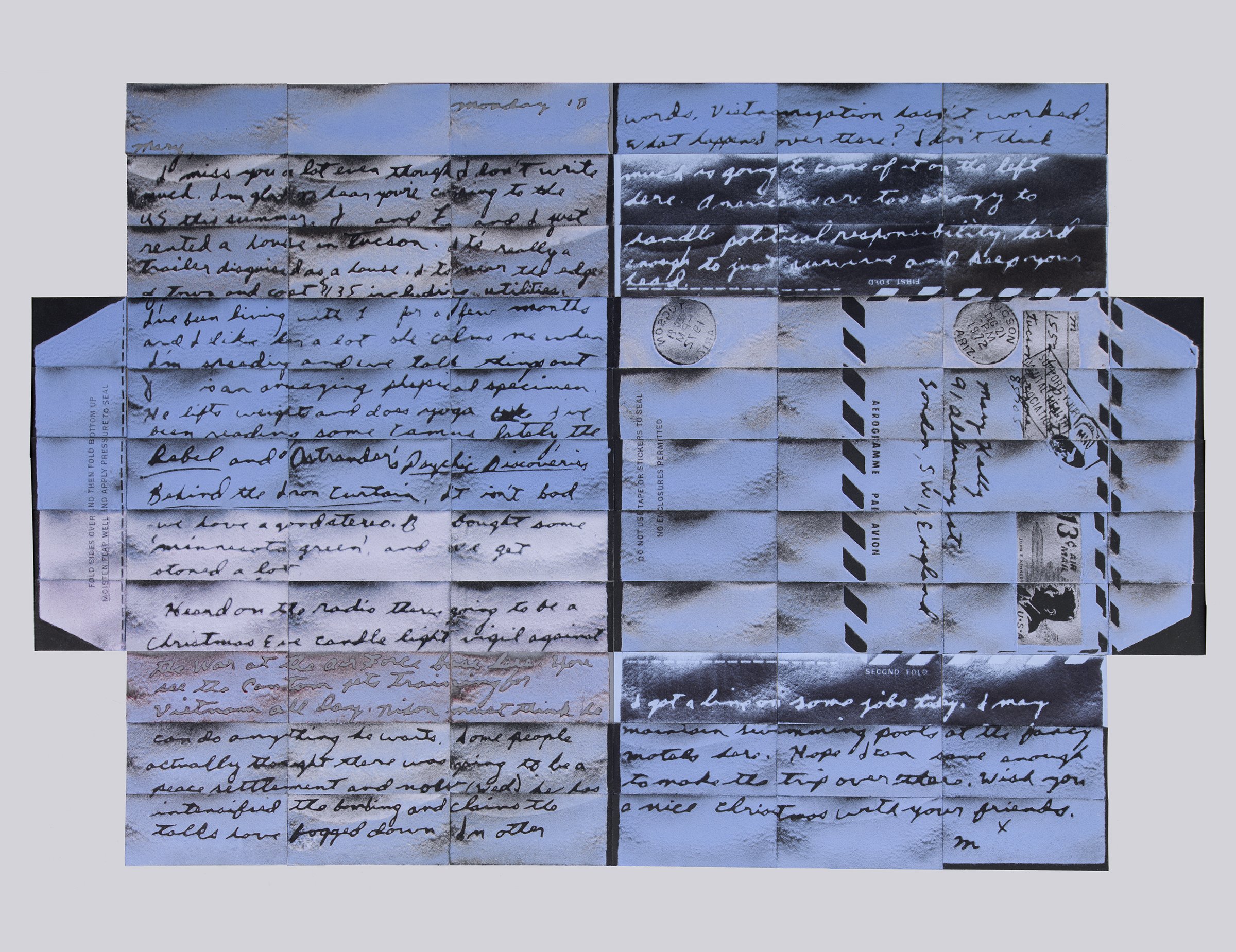

Mary Kelly

Tucson, 1972, 2017

Compressed lint

112 x 88 7/8 x 2 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

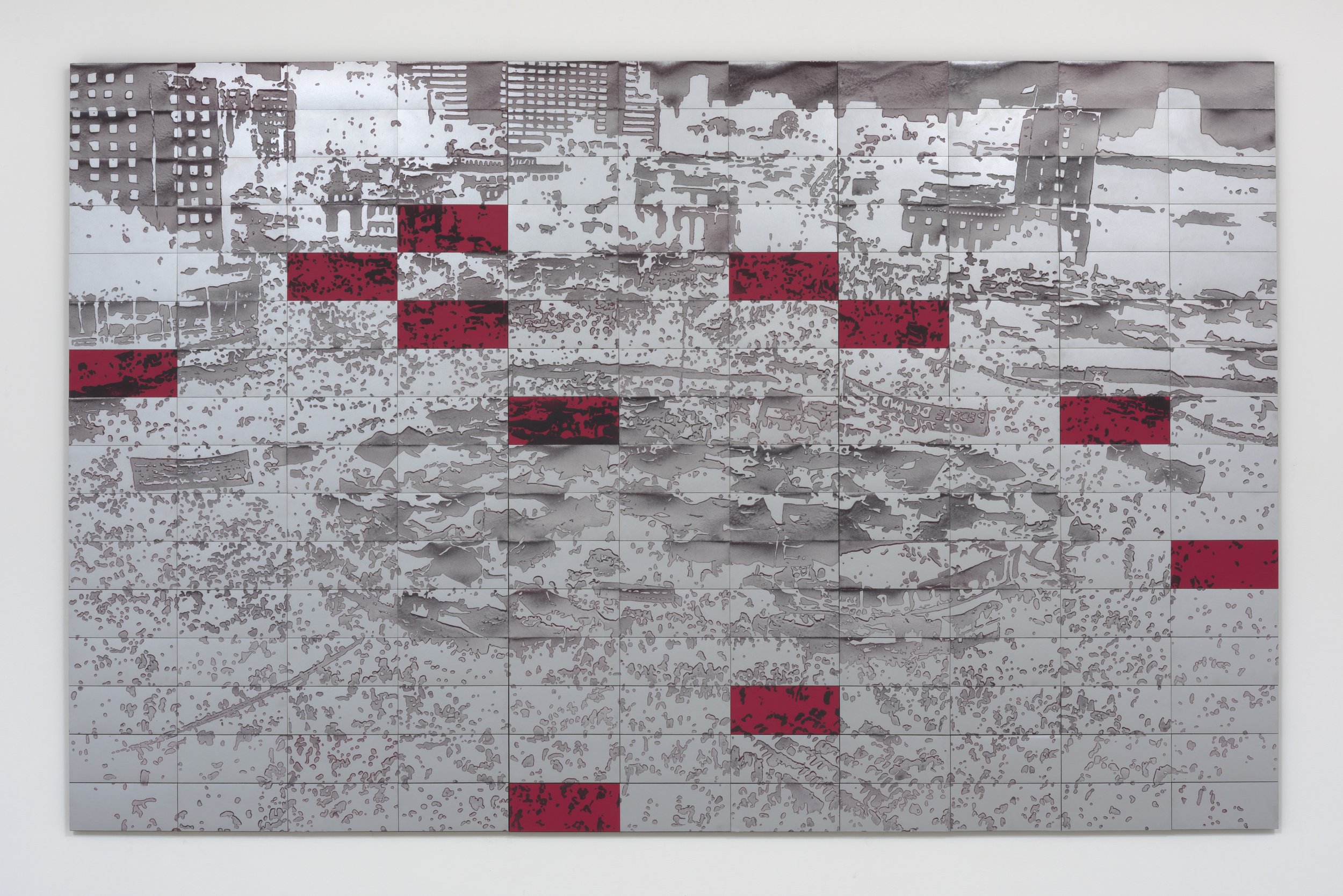

Mary Kelly

Circa 2011, 2016

Compressed lint and projected light noise

80 3/4 x 126 3/4 x 2 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

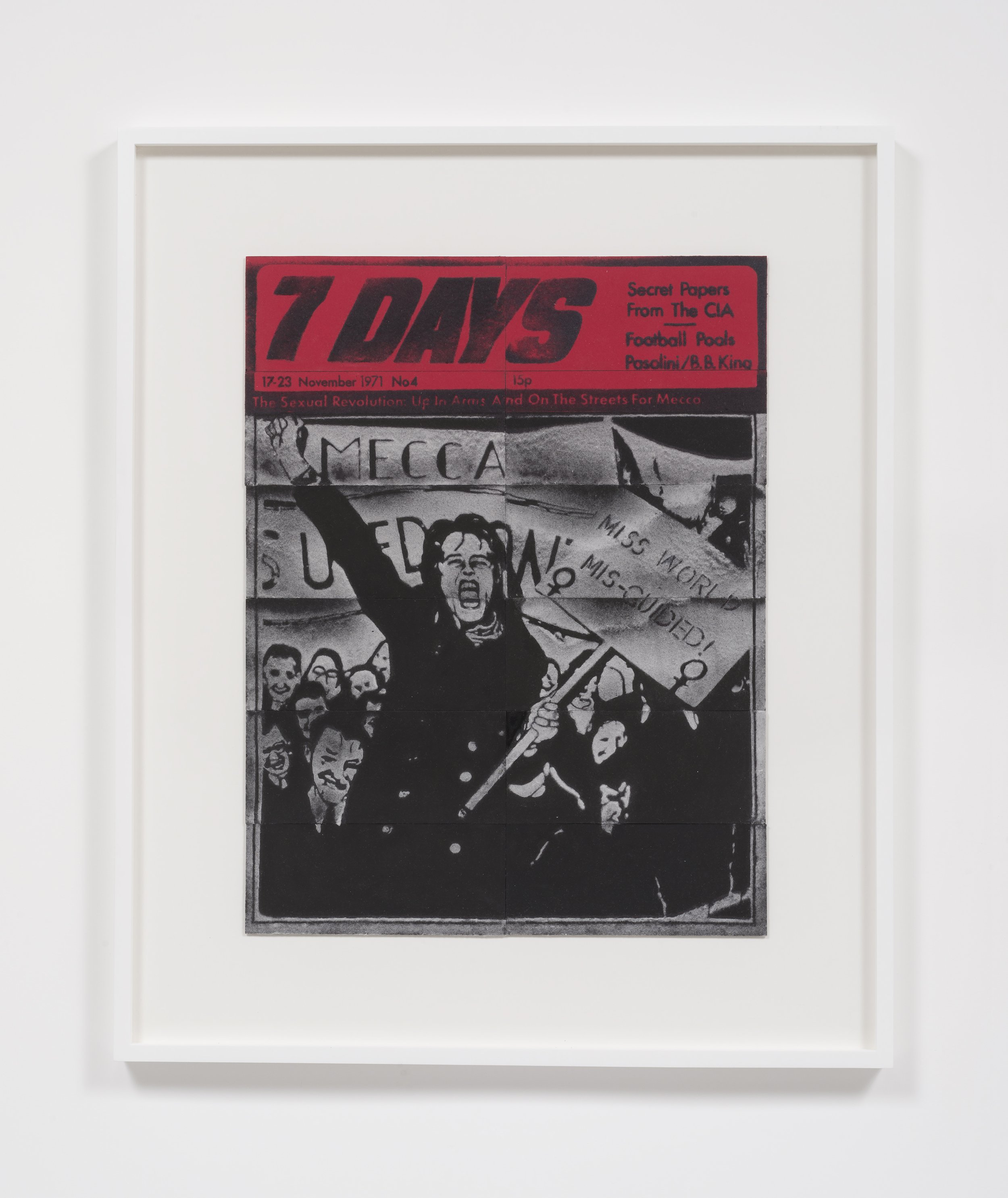

Mary Kelly

7 Days, 17-23 November, 1971, 2016

Compressed lint

41 1/8 x 34 1/8 x 2 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

Unguided Tour circa 1968, 2016

Letterpress prints on blotting paper

27 x 21 x 1.5 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

Mary Kelly

Circa 1968, 2004

Compressed lint and projected light noise

100 x 105 in

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell Innes and Nash, New York

Ramsey Kolber is an Assistant Curator for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi project living and working in New York. Previously, she served as the Curatorial Research Associate at the Whitney Museum of American Art working on the Museum's Collection Strategic Plan, a multi-year research project funded by the Henry Luce Foundation, focused on researching and assessing the Whitney's collection and outlining best practices for the future. Prior to this role, she served as the Curatorial Project Assistant for the 2019 Whitney Biennial working alongside co-curators Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta. In addition to her curatorial practice, she has held additional positions at the Brooklyn Museum; Chapter NY; Independent Curators International (ICI); and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. Her writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, Osmos Magazine, and 3rd Dimension, PMSA Journal as well as the 2019 Whitney Biennial catalogue and forthcoming Art for Rollins: The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art Volume 4. She holds an MA in Global Conceptualism from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, with a focus on early intersections between art and technology.

Mary Kelly is a Los Angeles-based artist known for addressing questions of identity in the form of large-scale narrative installations. In 1989 she joined the faculty of the Independent Study Program at the Whitney. Lacunae, her recent work, is included in the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Other works include Post-Partum Document, 1973-79, Interim, 1984-89, Love Songs, 2005-2007, and The Practical Past, 2016-2019. A retrospective of her work was organized by Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 2011. Major surveys were presented at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2010, Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, 2008, Generali Foundation, Vienna, 1998, Helsinki City Art Museum, 1994, and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, 1990. Her work was also featured in Desert X Biennial, 2019, Unlimited, Art Basel, 2016, Biennale of Sydney, 2008, Documenta 12, Kassel, 2007, 2004 Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Her publications include Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, 1998, Rereading Post-Partum Document, Generali Foundation, Vienna, 1999, Imaging Desire, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1996, and Dialogue, Iaspis, Stockholm, 2011. In 2015, she was awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, and in 2024, the Creative Capital Award. Currently, she is Judge Widney Professor in the Roski School of Art and Design, University of Southern California.