The Jumpsuit Project DC, 2019

Courtesy Maria & Alberto De La Cruz Gallery, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

one thing after another:

four notes on Sherrill Roland’s practice

by Kate Fowle

As is often the case, a chance snapshot of an event can reveal more than all the professional photographs put together. There’s one of those—taken in Sherrill Roland’s exhibition at the Asheville Art Museum in North Carolina in 2022—that captures the essence of an entire chapter of the artist’s life and practice.That chapter began in August 2012, when Roland entered the Studio Arts MFA program at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. Shortly after, a warrant for his arrest was put out in Washington,D.C.,with four felony counts against him. Over the next nine months, no indictment was issued, which resulted in his felony charges being reduced to misdemeanors. But in October 2013 he lost his bench trial, resulting in a sentence of one year and thirty days in D.C. County Jail, before being released a few months early, on “good behavior.” Almost a year and a half after his release, after a retrial, Roland was exonerated of all charges and granted a Bill of Innocence in December 2015. He then went back to UNC in 2016 and completed his Masters. In the end, the outcome of this dizzying turn of events over more than four years does not revolve around innocence or guilt. That doesn’t change the indelible impact of incarceration; the dehumanizing mental and physical abuse; the stripping away of identity; the confinement and isolation; and the ongoing prejudice and stigmatization upon coming home, where judgement persists long after “punishment” has been served.

Instead, what becomes imperative is how to regain control of one’s own narrative. How to process. To move forward. In subsequent semesters of art school, Roland honed dialogues around his experience through The Jumpsuit Project (2016–ongoing) which is a performative, community-engaged work, wherein he wore an orange jumpsuit around campus,“exposing my burden and vulnerability to an unsuspecting environment,”as he once described it (1). Engaging people in conversations around America’s broken criminal justice system, social contracts, identity, biases, and potentials for reform, the project gained momentum and continued after his graduation—in art world, educational, and public spaces—affording Roland national recognition. Then the COVID-19pandemic hit and “social-distancing” pressed pause on performance. Instead of using his voice and presence, Roland needed to fathom a new toolbox and make objects that could communicate his experience.He started using materials prevalent to his incarceration, such as the clear acrylic sheets used for partitions in visitation rooms, legal documents, correspondence with loved ones, and items available from commissary.

___________________

(1) This, and all other quotes taken from an interview with the author in February 2023.

Installation view: Sugar, Water, Lemon, Squeeze, Asheville Art Museum, 2022

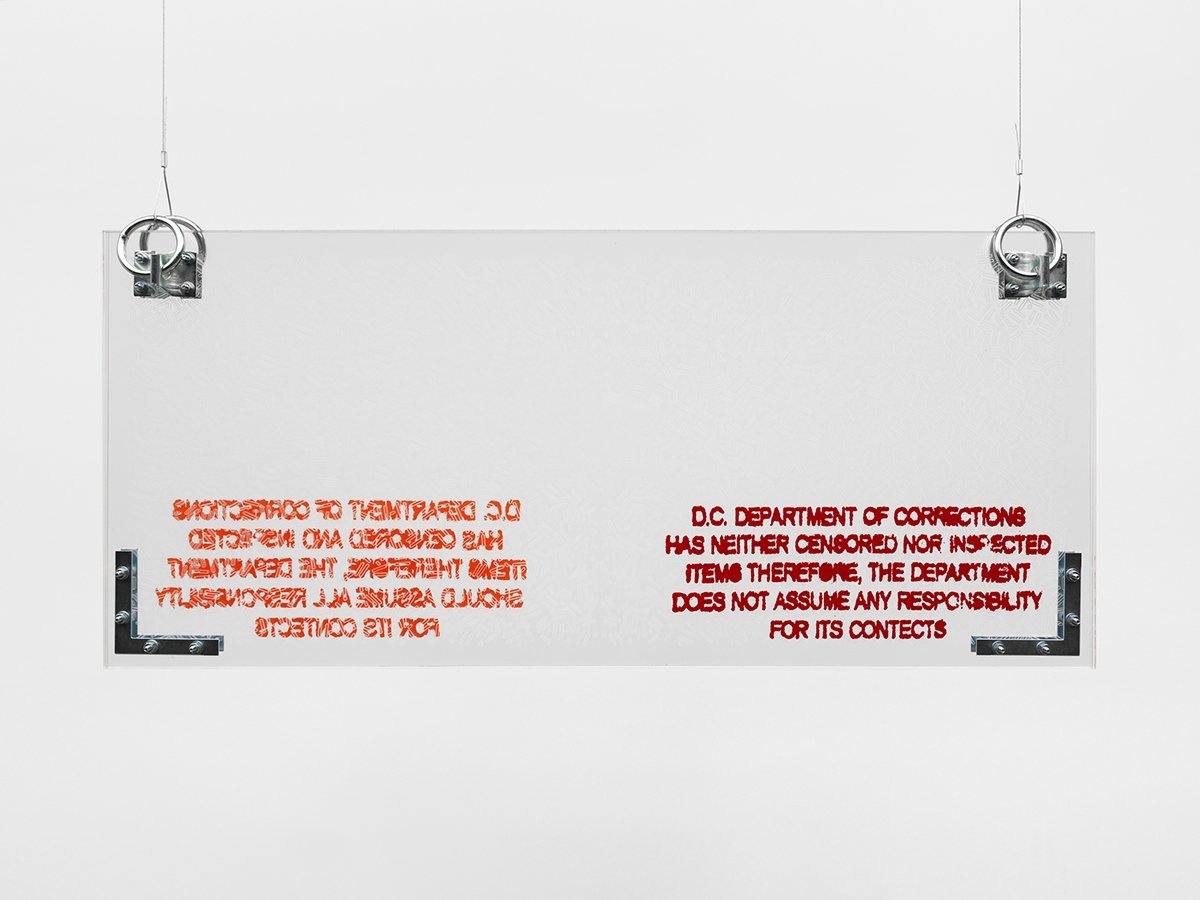

2. To return to that chance photograph taken in Sugar, Water, Lemon, Squeeze at the Asheville Art Museum: in the foreground there is a work from the series called DCDC Stamp (2021–22) which each have a unique subtitle in parenthesis: (spiritual), (physical), (mental), (emotional). They are hanging acrylic sculptures in the format of a security envelope, etched with versions of the mass produced, interior patterns designed to mask the envelope’s contents. On one side there is a text that’s stamped onto all outgoing mail from the jail:

D.C. DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HAS NEITHER CENSORED NOR INSPECTED ITEMS THEREFORE,

THE DEPARTMENT DOES NOT ASSUME ANY RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTECTS [sic]

On the other side, Roland has made his own version of the stamp:

D.C. DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HAS CENSORED AND INSPECTED ITEMS THEREFORE,

THE DEPARTMENT SHOULD ASSUME ALL RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTECTS.

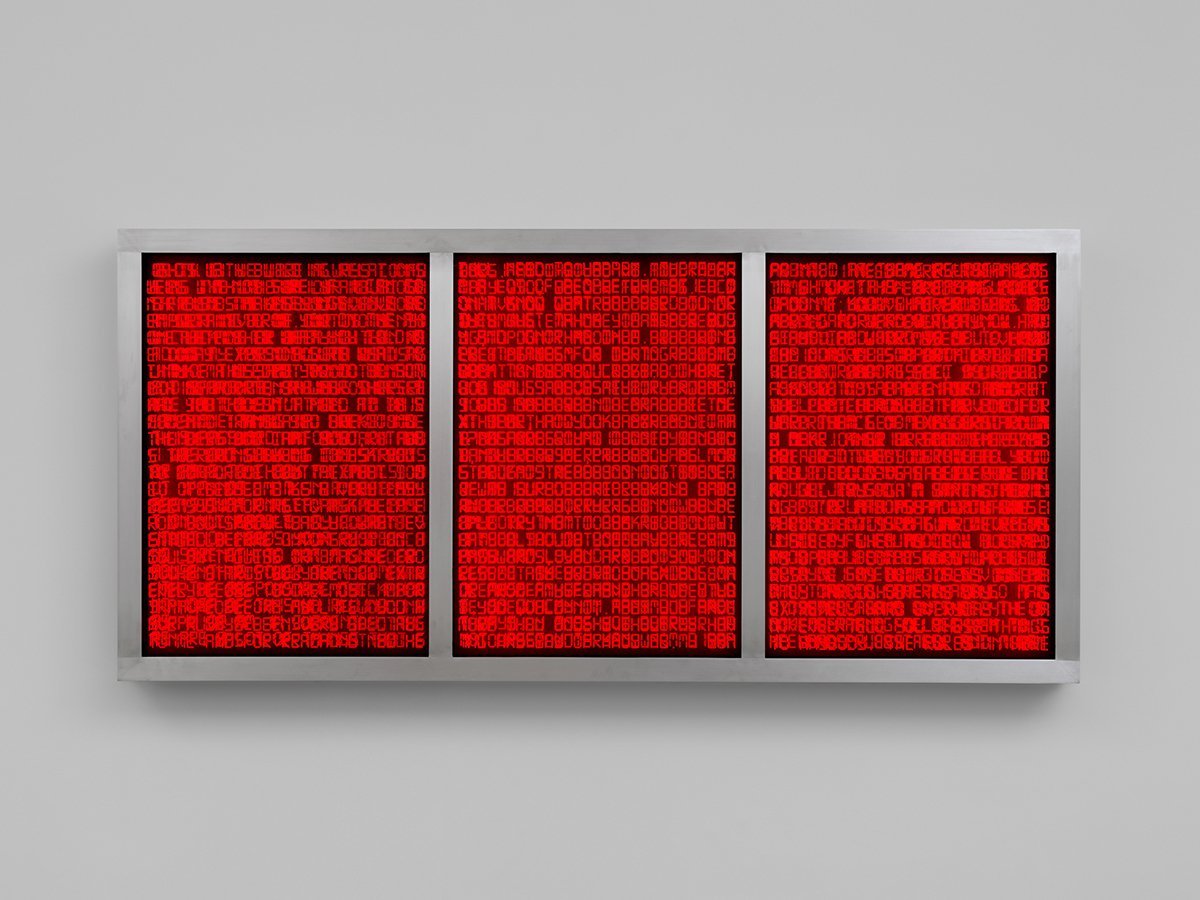

With those slight tweaks of the original text, Roland gives us commentary on his own release, which amounts to what he calls “a survivor’s tale,”as it does for many, in lieu of any rehabilitation upon reentry. He’s underlining how no responsibility is taken by the institution for anything—letters or people—once they leave the building. Meanwhile, what happens to the “contents” while inside is masked from public scrutiny. Due to the angle the photo was taken from, Roland’s altered text on DCDC Stamp (spiritual) merges into With Heart (2021–22), which constitutes a sequence of light boxes made of acrylic that are numbered with dates, such as #102813,#121313, and so on. Each is etched with text—extracted from Roland’s letters to his friends and family—using the LCD “digital clock” font.The text is layered to the point that it obfuscates personal details of the letters, but its density speaks volumes about Roland’s need to communicate, while the LCD font is a nod to the time that each letter helped to pass. If you were standing in the exhibition, the view afforded by this snapshot could easily be missed. It’s taken from one gallery looking “back” into the first space of the show, which is where documentation of The Jumpsuit Project was installed (those are the pieces you see hung to the right of the photo). The point I’m belaboring here is that the proximity of the three works eloquently makes evident Roland’s gradual withdrawal from telling his personal story as he gained distance from his carceral experience. In effect,With Heart and The Jumpsuit Project are bookends to a number of works undescribed here, bridged by DCDC Stamp, which signals Roland’s physical release. With hindsight, this photo—and indeed the exhibition in his hometown—signal closure on the first chapter of Roland’s practice.

“At a certain point I started playing with my own language. If there’s too much going on I have to peer more into that “sentence” and ask myself, what does it actually mean? What am I really after? That’s when I began world building.” — Sherrill Roland

3. In her book Passages in Modern Sculpture, written in 1977, art critic and theoretician Rosalind Krauss describes Minimalism’s ambition to shift “the origins of meaning in sculpture” from the “privacy of psychological space” to the “public, conventional nature of what might be called cultural space.” (2) Many artists at that time refuted the term Minimalism—Sol LeWitt instead coined “Conceptual” art, (3) Donald Judd preferred to use “three-dimensional work”—but they had consensus over moving away from the expressionism that consumed painting and sculpture after World War II. There was a need for a term that described, to quote Judd again,“that which is something of an object, and that which is open and extended, more or less environmental.” He goes on to explain,“Three dimensions are real space. That gets rid of the problem of illusionism and of literal space.[...] The order is not rationalistic and underlying, but is simply order, like that of continuity, one thing after another.” (4)

Roland’s series,168.+ (2022–ongoing) are the cornerstones of his world building. “More or less environmental,” they consist of both wall-and freestanding structures, each made of coated steel channels filled with color.168 refers to the dimensions of a cinder block—16x8x 8inches—the measurements of which define the distances between the angular turns of each works’ passage.

He recalls that the series started instinctively, as he searched his own lexicon. In the end they are very simple; the structures are white because that is the color of the blocks in D.C. jail that Roland used to trace with his finger, taking it on a journey through the channels of mortar. It’s the artist’s playful renditions of this action that demarcate the form of each work.

The colored, acrylic-medium-bound “mortar” is made from various Kool-Aid flavors—168.808 is filled with Lemon-Lime,168.811 is Strawberry Kiwi and Peach Mango, and 168.815 includes the three colors Jamaica/Lemonade/Lemon-Lime, for example. Oftentimes the shift between colors on a spectrum are barely discernable from a distance.Who knew that Kool-Aid Grape and Black Cherry were so similar? Then, the last three numbers of the titles are the last three digits of zip codes in Asheville, where Roland grew up. He uses them because of the connections he makes between Kool-Aid and memories of childhood.

As his audience, the artist doesn’t need us to have all this information as we approach the work, nor do we get told the various Kool-Aid flavors in the works’ materials list on the label. We don’t have to know Roland was incarcerated, or exonerated, that he is from North Carolina, or color-blind, or a father, or likes African painted dogs and going to the Asheville Smoky mountains. While he remains focused on using carceral materials as his “toolbox,”now they have become the grammar and syntax of his practice, as opposed to the story line. As Judd said, “it is simply order, like that of continuity.”

_____________________

(2) Rosalind Krauss, “The Double Negative: a new syntax for sculpture” in Passages in Modern Sculpture pg 270. Viking Press, NY, 1977

(3) Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” in Artforum International pp 79-83, Summer 1967, Vol 5, No 10.

(4) Donald Judd, ”Specific Objects,” in Contemporary Sculpture: Arts Yearbook 8 pp 181-9. Edited by William Seitz, The Arts Digest, NY, 1965

4. “There is a perceived idea that a work of art was made from your imagination and from your intuition. I do believe that there is such a thing as intuition and there is such a thing as imagination. I just think these are concepts that are culturally realized. What we come to understand as knowledge and meaning are not pure products of our genius but are built into the structure where we reside.” — Charles Gaines, quoted from Systems & Structures, Art 21

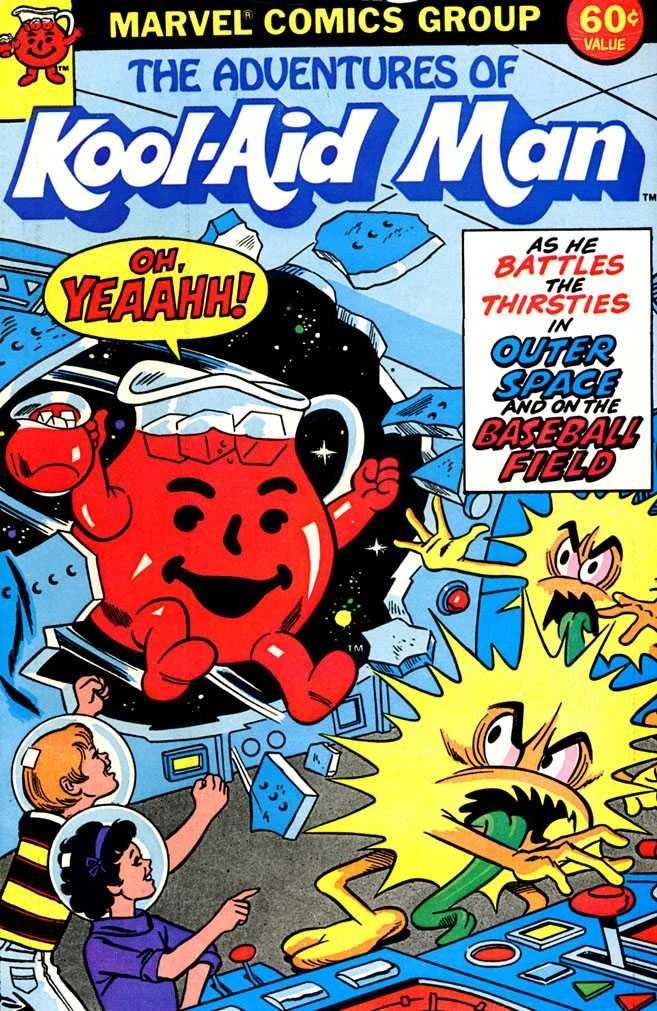

Collectively referred to as the “Kool-Aid smiles,”KoolAid? No Sugar (2022) and Smile and the world smiles with you in return (2022), are inspired by the patterning of the Ishihara Test, a color vision assessment which detects red-green color deficiencies. In Roland’s versions, the dots are Kool-Aid colors, which instead of masking numbers, test your ability to see the smile of the Kool-Aid Man. While aesthetically alluring, on multiple levels the works are also perfect examples of Charles Gaines’s notion of “culturally realized” works, which in turn echoes and builds on Krauss’s suggestion that the minimalist ambition was to shift sculpture to “what might be called cultural space.” As someone who grew up in the U.K., I am playing catch up with who the Kool-Aid Man is, let alone detecting his smile concealed in a vertical stasis within the works. But for Roland, you don’t need to know the specifics of the character. Instead, he’s seeking engagement with broader notions of duality, of camouflage, and of recognition. As part of the process of honing his language, he thought more deeply about why Kool-Aid held significance for him. It wasn’t just childhood memories in general, but those of safety in connection to home and family.It was a place where he was at once seen and masked: hidden in plain sight.

Then there are more recent examples of rare affinities Roland drew upon, such as meeting another exoneree or someone with the same red-green impairment, and feeling the comfort of fleeting communion when a person looks at the work and knows exactly what he means without explanation. In the artist’s words: “The notion of a test is about looking with your own eyes, and hoping that the thing you're searching for will reveal itself, right? It’s having the ability to recognize something through layers because you see straight through them.”

The most recent “test” series are visually more akin to the Rorschach psychological evaluations, while continuing to mine the world of Kool-Aid Man. It turns out that for a brief moment in the eighties the character was subject to the Marvel Comics treatment, bursting through walls as the“Quencher of Thirst,”coming to folks’ rescue when the menacing “Thirsties”—who look like evil suns with long, panting tongues—tried to parch people, depriving them of simple pleasures and needs in various dastardly ways. In a series of diptychs and large landscapes, Roland relishes elongated tongues that visibly burst out of a conglomeration of yellow spots.This is Roland’s first go around with presenting the“dark side,” and as with the saccharine nature of comics, there is much lyricism to be had. The titles are also getting more intriguing: I remember nights, I didn’t remember nights (2023),Walking around just hoping to get one more try to make it (2023), and But we stuck here ‘til we get there (2023). At the time of writing, these new pieces areas yet not fully completed, befittingly left as a cliff hanger...I’m looking forward to seeing how these series evolve and I’m sure this chapter is far from over, even though others are being drafted and new paragraphs are already for the public eye. There is a momentum and confidence in Roland’s visual stride that is exhilarating to see. To me, there is also a growing sense of location and belonging that his work exudes. I’m going to leave these notes on another quote from Gaines—an artist whom Roland deeply respects and with whom I see he has close affinities—as a way to put future chapters into the universe. One thing after another:

“Even people whom I really liked—Cage and LeWitt were visionaries—were suspicious of letting language get out of control.It was important to protect visual or sound culture from that.I was just the opposite.For me, an artwork is the impetus for letting language get out of control—letting dynamic experiences happen.[...] I was precisely interested in the excesses of language. My use of systems is not as an empirical or documentary tool. I use systems in order to provoke issues around representation.” (5)

________________________

(5) Courtney J Martin in conversation with Charles Gaines, “Five Will Give You Ten” in Charles Gaines, Grid Work 1974-89, pg 35. Studio Museum in Harlem, NY, 2014.