from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 11

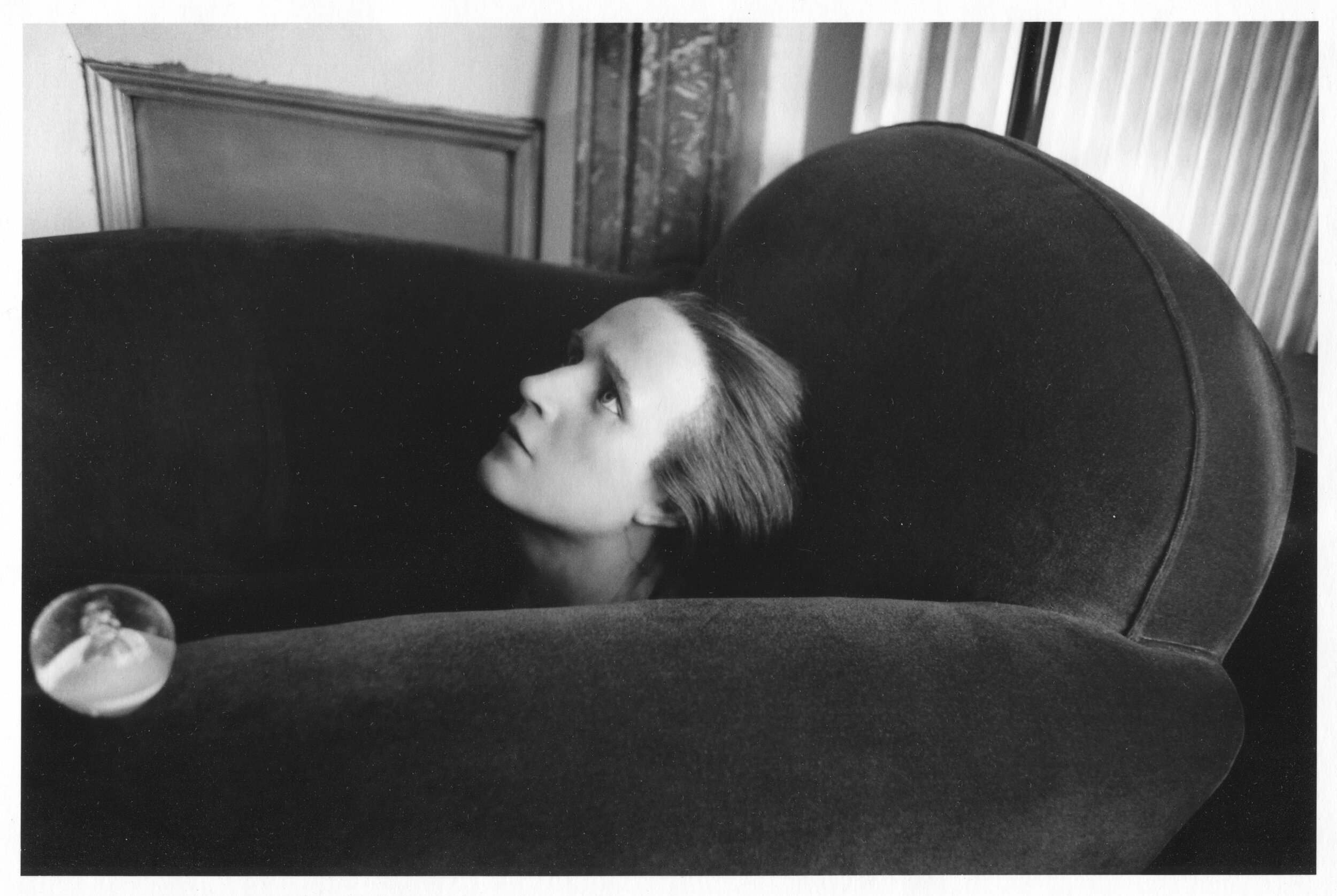

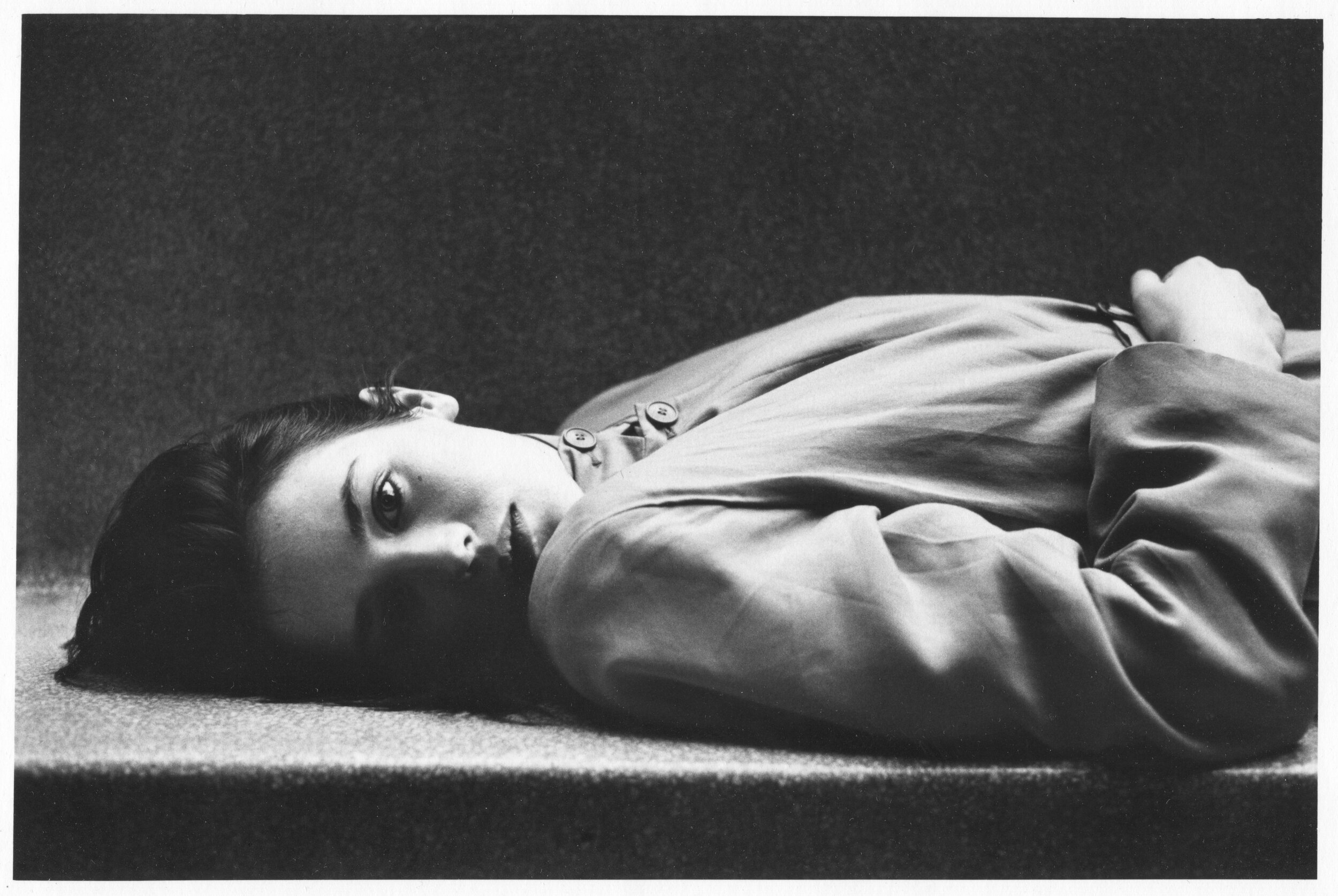

HERVÉ GUIBERT

Introduced by his Gallerist

Photios Giovanis

Autoportrait, rue du Moulin-vert, 1981

La tête de Jeanne d'Arc, 1982

It was February of 2013 when Stephen and I went to Paris to meet with Agathe Gaillard, the owner of the eponymous gallery that has been exhibiting Hervé Guibert’s photographs since 1980. Joining us was Christine Guibert, whom Hervé married toward the end of his life, and who was a close friend when she appeared in several of his photographs. We were first introduced to Agathe and Christine by the writer and translator Nathanaël, who was working on an English-language translation of Guibert’s journals, The Mausoleum of Lovers, which my partner Stephen, the publisher of Nightboat Books, was planning to publish. Our idea was to exhibit Guibert’s photographs at the gallery to coincide with the release of the book. Years prior to this, I remember coming across Guibert’s book Ghost Image (published by Sun & Moon) at City Lights in San Francisco. I didn’t buy the book. I had since forgotten Guibert and so I was learning about him—his writing and his photographs—for the first time.

Just days before, Jason Simon, Moyra Davey, and I were in the gallery on Forsyth Street catching up. The Forsyth space was shaped like a loaf of Wonder Bread, the first slice of which is made of glass—the window faces a park. Jason has had two exhibitions at the gallery of which I am particularly proud and which brought a certain amount of continuity with Jason’s prior work with Orchard Gallery (and with his earlier exhibitions at American Fine Arts and Pat Hearn). When Jason asked why I was traveling to Paris, I shared that Stephen and I would be meeting with the executor of Hervé Guibert’s estate and his gallerist there to talk about the forthcoming book, with the hope of organizing an exhibition in New York. Coincidentally, Jason and Moyra had been introduced to Guibert by friends (also artists) less than a year before while viewing the Francesca Woodman exhibition at the Guggenheim. Moyra was working on an essay about her own work that ended with observations about Guibert after several passages through the work of other photographers. The Mausoleum of Lovers was not due to be out for some time, but Jason recommended that I move quickly to show Guibert’s photographs and suggested a group show as a first step. Our accidental confluence around Guibert led to a show organized by Jason and Moyra about a larger network of associations between artists who work with photography.

Stephen and I wander down from our Marais studio to locate the gallery, but were a full day early for our appointment. A few black-and-white framed photographs are propped up in the window bays of the gallery’s red storefront. We peer inside to see that the walls of the space are painted a deep gray. Framed photographs hang from wires against walls that are lined with shelves that hold large archival boxes. A large table in the center displays catalogs and postcards.

Thierry, 1979

Sienne, 1979

For Guibert photography has a particular relationship with skin. A photograph can reveal something of what lies beneath, opening a view into subjectivity. But what I find extraordinary about Guibert's view is that while photography can breach this border-organ separating inside from outside, a photograph can also have just as much materiality as a body. It is a body comprised of image, paper, and gelatin emulsion. The erotics of this materiality and this breach is illustrated in an account Guibert gives of the sole photograph that he keeps in his apartment, an account titled The Cancerous Image. It closes the collection of essays that comprises Ghost Image with an echo of The Picture of Dorian Grey. The photograph he kept, and ultimately destroys, is not a photograph he took himself but one he stole from an acquaintance’s apartment.

We arrive at the gallery the next day at our appointed time to meet with Agathe and Christine. After some introductory comments, she shows us the gallery’s inventory of Guibert photographs, which filled several archival boxes. Each photograph was housed it its own creamy paper sleeve. While looking at the photographs, I was struck by his self-portraits which where interspersed throughout the larger body of work. In one photograph Guibert looks directly at the camera, while his two aunts are behind him looking somewhat distant, as if they are waiting; one stands behind him, the other sitting next to him in a chair. They are surrounded by the patterns of the wallpaper and upholstery of the furniture. Guibert, in his youth, looks fresh and smooth, with a pile of curly hair on his head. This is both a family portrait and a self-portrait. But the emphasis on his aunts displaces the usual familial frame- works that produce generations.

Guibert thought of The Mausoleum of Lovers as a novel, a series of undated entries that trace the arc of his life, his writing, his photographs. Although his life was cut short by his suicide in the face of serious illness brought on by AIDS, he embraced the fragmentary and photographic sense of time that pervades this book. Looking at the photographs, I realized that gathered together, they too told the story of his brief life. Looking at the photographs at the gallery, moving through the stacks of them one by one, I realized I was touching the prints that Guibert himself had handled. His skin had handled these pages, just as he had handled the pages of his notebooks. This collection in the gallery was a mausoleum of its own, a monument to his own brief life.

Isabelle, 1980

Autoportrait, rue du Moulin-vert, 1986