from the archives

Excerpt from OSMOS Issue 20

Live streaming, Prince Edward, 12/11/2019, 23:35:05-6. 25 frames per second, 1920 x 1080, 2019

WEI LENG TAY

LIVE STREAMING, PRINCE EDWARD, 12/11/2019, 23:35:05-06

BY KATHLEEN DITZIG

A boy at Repulse Bay beach during SARS, 2003. Kodak E100VS slide, 35 mm, 2019

A television is on in a living room cluttered with toys and the haphazard accumulation of a busy family’s things. Presented as twenty-five stills, the work, Live Streaming, Prince Edward, 11/12/2019, 23:35:05–06, is one second of video documentation that Wei Leng Tay made of live streams of political protests on November 12, 2019. It is a series of images inspired by a photographer’s existential crisis—a consideration of what it means for an artist to respond to systemic shifts in Hong Kong society and, more broadly, the geopolitical structure of the world. Live Streaming ... is a consideration of what it means to photograph today.

A few days before Tay recorded this footage, a boy died. Chow Tse-Lok was the first fatality of the protests in Hong Kong. As a result, public trans- port was suspended and people stayed at home. They watched the protests from an array of screens: televisions, computers, and smart phones filtered images that made each living room a theater and its inhabitants active spectators held in a collective suspense. Around-the-clock reportage on the networks and social-media updates were posted and reposted, constituting and reconstituting narratives and framing the ways in which the protest was seen and understood. What does it mean to photograph in this deluge of images? What does it mean to add another image? In the living room, Tay watched a man being beaten up—un- sure if what she was seeing was another act of unaccounted brutality, even another murder. Live Streaming... was, in effect, a response and a refusal to photograph.

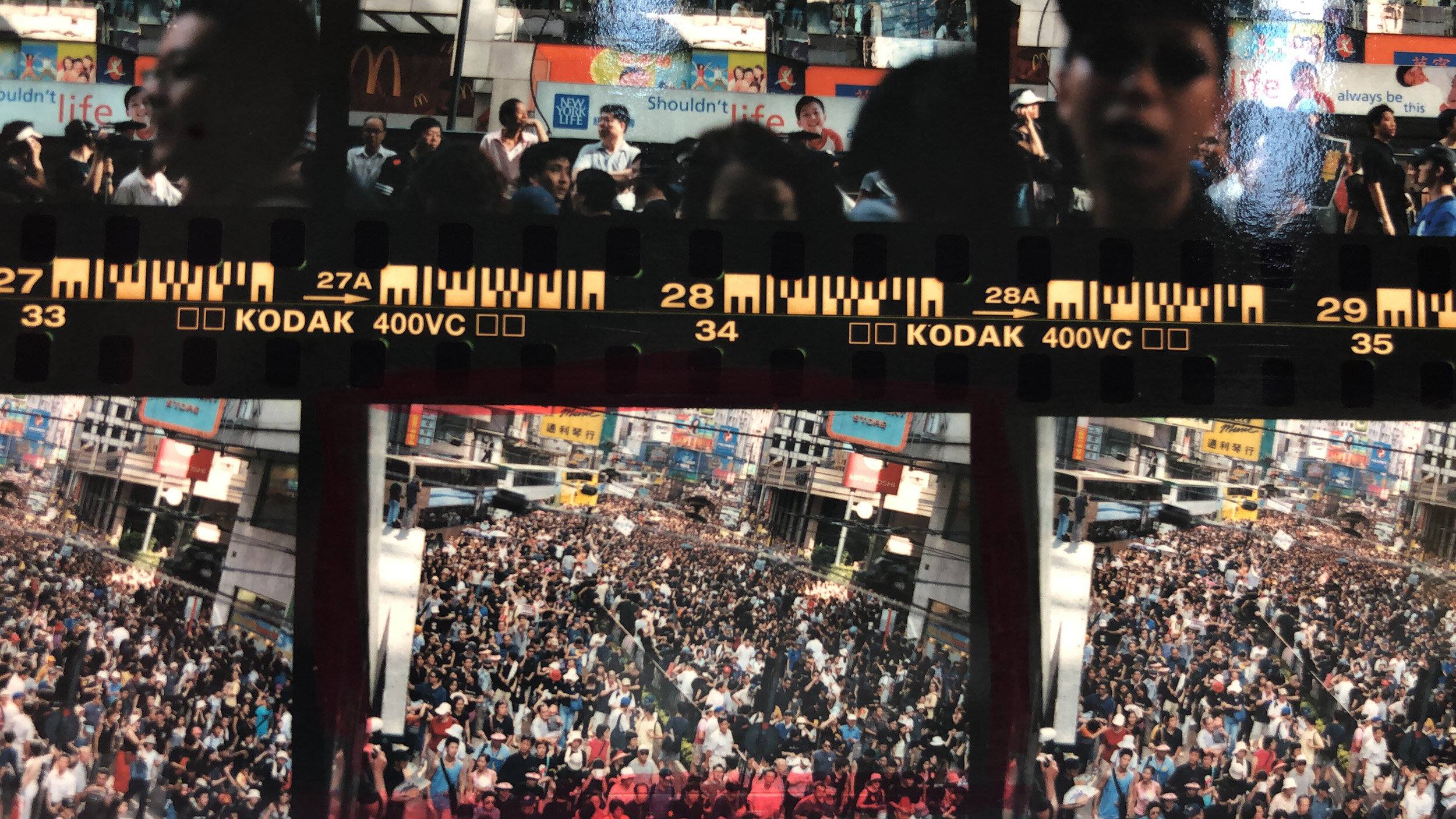

Tay interrogates the ways in which the photograph mediates the world we live in. Her projects are personal and are informed by current affairs. Tay moved to Hong Kong in 2000 and worked as a photographer and photo editor with American news organizations there until 2014. She contextualized the news. Her photo- graphs of Hong Kong captured key moments in the city's history. For example, in 2003, on assignment for Time, she documented crowds throng- ing the streets in what was then the largest demonstration since the 1997 handover. People were protesting Law Article 23, which was viewed as infringing upon Hong Kongers’ ability to speak out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Her photo- graphs also imagine Hong Kong through a neighbor’s home, through pedestrians on the street, or through small details such as a missing street sign.

Whether re-photographing the work as a contact sheet, or including the reflective glare of plastic covering, or simply by rendering a moving image still, Tay considers not only the photograph as a form of mediation but also its material form. Her image-making reflexively makes itself material, registering the realities of its making, distribution, and place in the world. Tay’s hand and iPhone, which she uses to re-image her work, are blurry specters that speak to historical shifts in photo-making, a dissonance between the past and present of photography. In re-photographing her previous work, Tay reimagines and re-images the photograph itself.

Returning to Live Streaming...: Above the gleam of the screen is a framed photograph by Tay—a gift given some time ago to Tay’s host and friend, which hangs as if it was stacked above the TV. The framed photograph, which is difficult to discern, is of the place Tay lived in Hong Kong in the 2000s. It is history sitting upon the contemporary. In Tay’s refusal to photograph the protest on the street, she instead makes an image of a collective experience of protest lived through mediation. It is part of her material registration of the epistemological demands of the photograph. These twenty-five stills materialize Tay’s refusal, her desire to critically engage with what it means to photograph and what it means to see through the photograph as a historical object.

Article 23 protest, Causeway Bay, 1/7/2003. Contact sheet, Kodak 400VC negative, 35mm, 2019

Kai Yuen Lane missing sign, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120 mm, 2019

Young woman in front of Circle K, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120 mm, 2019

View from Kai Yuen Street, date unknown. Fuji RVP100F slide (Kodak E100VS discontinued), 120 mm, 2019