Originally published fall 2016.

Introduction by Eugenia Bell

Slava Ukraini, Heroem Slava! (“Glory to Ukraine, Glory to Heroes!”) This is the customary greeting among Ukrainian nationalists. Its origins are in the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917–21), and it regained popularity during the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution, serving as a reminder of a country’s fragile identity and its long history of fighting to protect it. Soldiers, private militias, nationalists, and volunteer battalions fighting in Ukraine’s interest remain fractured to this day.

It is easy to believe that events in Ukraine (mildly and nimbly described by the media as “Russian aggression”) have slowed down, or that they have even ceased to occur. The colossal speed of the media cycle has diverted attention away from the crisis in the Crimea, first to Russia’s role in the Syrian crisis and more recently to the contributions of (and to) a Trump campaign operator in the leveling of Ukraine’s independent government. Like many foreign conflicts, the depths of history, the blurred lines, and the psychic distance from our own experience isolates the situation and places it somewhere above a minor political scandal and below what a Kardashian is reading. But the crisis continues and while it has been actively covered in the news media over the past two years, we seldom see a human side to it, or profiles (visual or narrative) of its primary players—not the politicians, not the Russian army, but Ukranians in the midst of the revolution. Two-and-a-half years after the events of the Euromaidan Revolution led to the toppling of Ukraine’s government, many of the subjects portrayed here—once inspired by a nationalistic hope—are now uncertain of the fate of their country.

Amid a broken ceasefire in an ugly war against pro-Russian separatists who reject the post-revolutionary government, Heroem Slava is Brian De Pinto’s first entry in the young American photojournalist’s ongoing series exploring the soldiers and nationalists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of eastern Ukraine. Embedded in a muddle of factions, histories, and languages, De Pinto boldly insists that the subjects are the story, but his investigation is also a testament to the tenacity and sincerity, and accompanying doubt, of being a young, ambitious-yet-naive photojournalist who is not a little scared in the face of the unknown. Below is an edited excerpt from De Pinto’s travel diary, written in the summer of 2015, when most of these photographs were taken.

A bridge destroyed by fleeing pro Russian separatist forces in Sloviansk, Ukraine.

An SNAR-10, used by the Ukrainian Ground Forces, Novooleksandrivka, Ukraine.

Soldier, artillery battalion of the Ukrainian Ground Forces bearing a cossack tattoo and hairstyle in Novooleksandrivka, Ukraine.

Soldier, artillery battalion of the Ukrainian Ground Forces, Novooleksandrivka, Ukraine.

Rem, Commander of the 7th battalion of the nationalistic group Right Sector in Vodyane, Ukraine.

A masked soldier stands guard at a checkpoint in Karlovka, Donetsk region, Ukraine.

A woman asks for food outside of Avdiivka, Ukraine. Shelling attacks thought to be coming from the separatist side were believed to be the cause

Owl, Soldier of the 7th battalion of the nationalistic group Right Sector in Vodyane, Ukraine.

A home lies in ruins after a battle outside of Kramatorsk, Ukraine.

From De Pinto’s travel diary, written in the summer of 2015, when most of these photographs were taken.

Operating with a fixer has been beneficial and incredibly frustrating. Pushy at times and not allowing me a moment to think but also helping to arrange amazing access that might not have been possible otherwise. I sold my 24-70 before I came here and have since realized that was a mistake. Moments I wish I could capture go passing by. I’m either too far and by the time I get close the moments is gone, or I have a 50mm lens on and am to close to capture it all. Words can’t describe how frustrated I am with myself at times. I can be my own worst enemy. Causing more problems and headaches then I care to admit. I’ve often found solo wanderings to be the most inspirational and productive. Here, tethered to a fixer most time and unable to speak the language with a people hesitant at times to speak to journalists. Often times my passive nature can cause problems as well.

Halfway through this trip, after a few days of thinking and looking at the subjects I have access to decided to shoot mostly portraits of soldiers on medium format film. There are few subjects here that haven't been covered. Recreating the photos at the same places with the same subjects I’ve seen come from this area seems redundant and unoriginal. It becomes more and more evident everyday since I’ve been here that the ego and self-absorbed nature of the West or at least of New York has become too much for me to handle. I continually ask myself the same question I began this paper with. Why did I come to Ukraine? To prove myself a brave man and photograph war? To prove myself a great photographer? I say it is to tell the stories of the people, but I have no audience to speak of . . . no publication behind me. No idea what the hell I am doing. The only reason I can honestly say I am here is to further my own agenda. No way around it. I’ve found myself sick at the thought. What the fuck am I doing? This war isn't as clear-cut as I would hope. I find myself siding with the Ukrainians, but I also know or at least think I know that the government is terribly corrupt. The Russians meanwhile run a propaganda machine convincing their people that the Ukrainians are fascists and Nazis. One report going as far as to say that the Ukrainians are fighting to take land and slaves. The idea of war fascinates me as it must most young men who take the time to look into it’s integral role in our civilization and the dividing up of our planet. Yet, coming across the world I cower at the face of war. Given the opportunity to go to the front lines terrified me. The idea that I am untrained fighting with an informal military in a war I have nothing to do with were surely factors. I read an interview with Adam Ferguson yesterday that mentioned his time during the Bangkok protests. How the world may never have another photojournalist like him. How the world and its digital media may not need a pack of roving photojournalists to tell its stories. The world can tell its own stories. Well, I read that and I, in some cases, can’t help but agree. But I must ask. Where does that leave me—someone looking to do work of this nature? Someone just starting out but with only the legacy of those who came before to guide me. Lost in a vacuum battling my own ego, unsure of where to turn or what to do or how to do it. That’s where I am left.

A prosthetic leg stands in front of drawings sent to raise morale for Soldiers in an army medical hospital in Artemivsk, Ukraine.

Surgeon of the Ukrainian National Guard, Artemivsk, Ukraine.

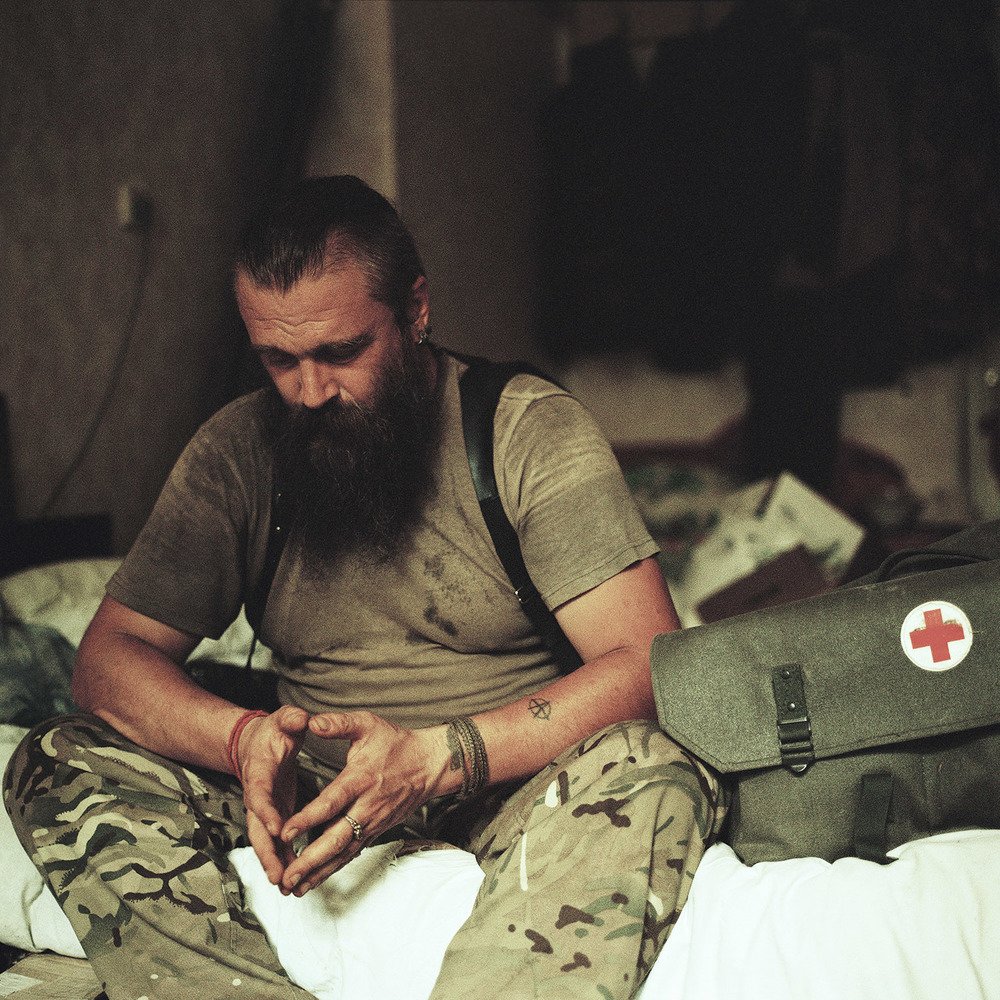

Medic, Ukrainian National Guard, Artemivsk, Ukraine.

Rem with duck, Vodyane, Ukraine.